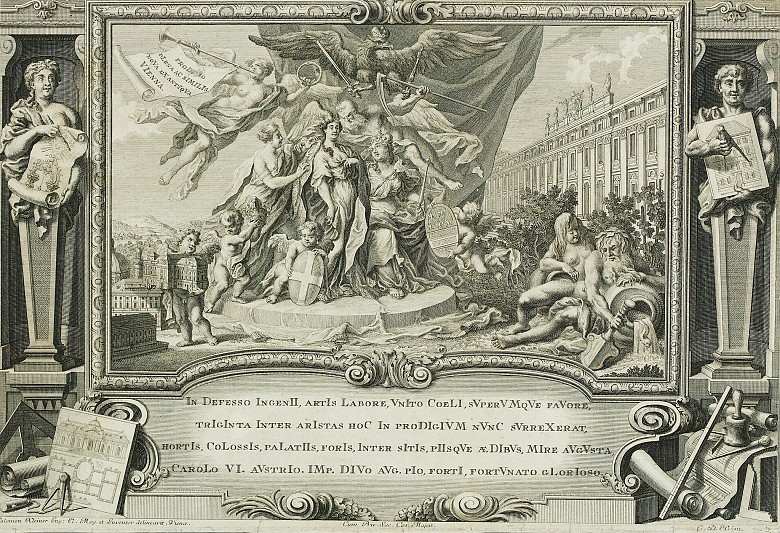

Vienna Gloriosa: The grandiose projects of Charles VI

When Charles VI ascended the throne, the Vienna Hofburg, which was after all the residence of a monarch who could lay claim to the leading role in Europe, was an antiquated assemblage of wings and sections of different ages and varying quality. The last large-scale alteration, the building of the Leopoldinischer Trakt, had taken place more than half a century previously.

Quoted from: Lorenz, Hellmut: ‘Nichts Brachtigeres kann gemachet werden als die vornehmen Gebeude. Bemerkungen zur Bautätigkeit der Fürsten von Liechtenstein in der Barockzeit’, in: Oberhammer, Evelin (ed.), Der ganzen Welt ein Lob und Spiegel. Das Fürstenhaus Liechtenstein in der frühen Neuzeit, Vienna 1990, 138-154 (here 144)In his treatise on architecture entitled Werk von der Architektur (c. 1675), Prince Karl Eusebius of Liechtenstein explains the intention behind the architectural commissions of aristocratic patrons:

This is then the sole and highest occasion of these noble and stately buildings: the immortal name and glory and eternal remembrance that is thus left behind by the structore [founder] ... Everything passes away and spoils and decays; only the noble edifice endures.

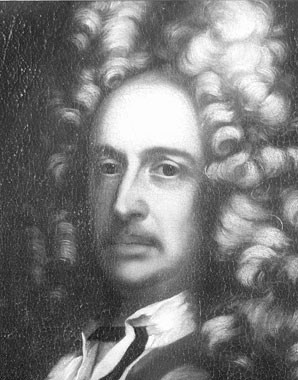

This is all the more astonishing if one considers that in the Baroque era it was architecture in particular that was regarded as the best means of representing power. However, the imperial court architect, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, who had won a reputation as specialist for monumental projects with his first sensational set of designs for Schönbrunn, was able to realize only a few projects for the ruling dynasty as the state finances were tied up in the War of the Spanish Succession.

Nonetheless, the years following 1715 saw a huge building boom when Charles VI initiated a number of important projects in and around the Hofburg.

The first project to be realised was the Court Stables (today the MuseumsQuartier), which with its colossal main façade measuring more than 300 metres was erected outside the city walls as a counterweight to the Hofburg. Based on the large edifices of classical Roman architecture, it was however a much smaller version of the utopian design originally conceived by Fischer.

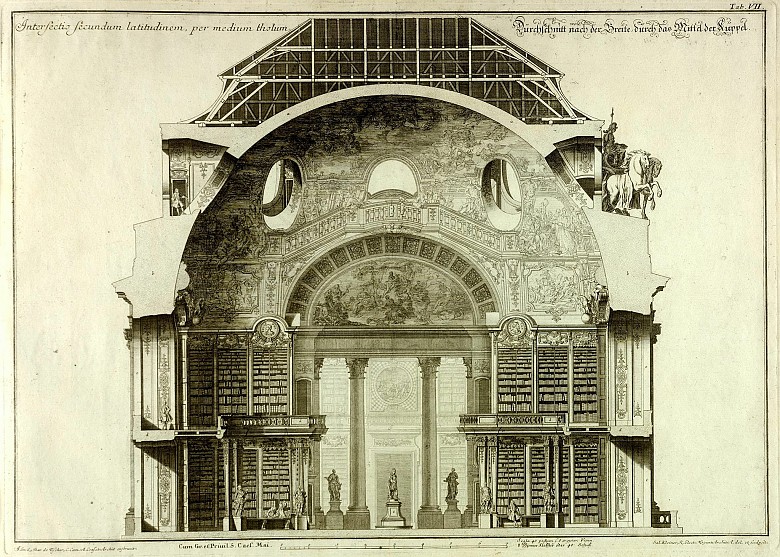

The Court Library is regarded as Fischer’s late masterpiece, its dimensions and formal language representing a unique testimony to the Habsburg claim to dominance in cultural affairs. A statue of Charles VI in classical pose still stands at the centre of the library’s Great Hall, representing the emperor as the protector of the arts and sciences.

After Fischer’s death in 1723 his son Joseph Emanuel took over his position as Court architect, continuing his father’s projects and adding to them with designs of his own.

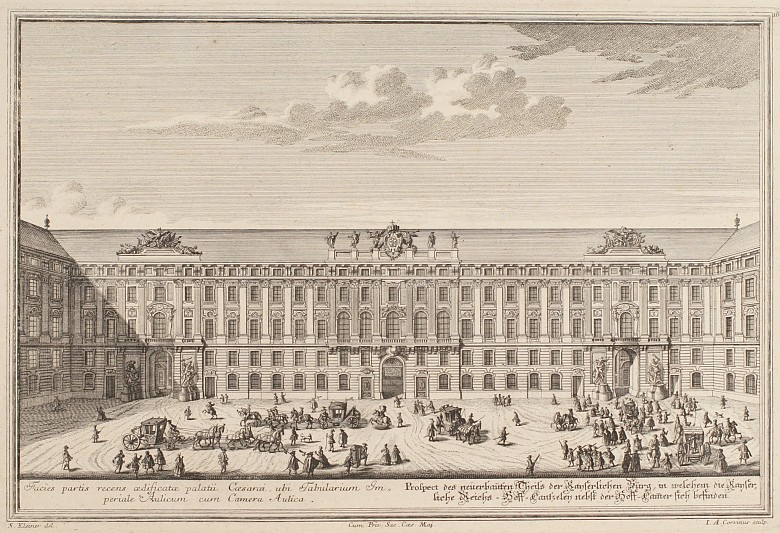

He was responsible for the building of the Reichskanzleitrakt (Imperial Chancellery Wing), the two-dimensional design of its monumental main façade taking account of the older wings around the inner palace courtyard.

The ceiling construction of the spacious arena of the Winter Riding School was one of the finest technical achievements of its day. For a long time it was the largest unsupported ceiling span in Vienna.

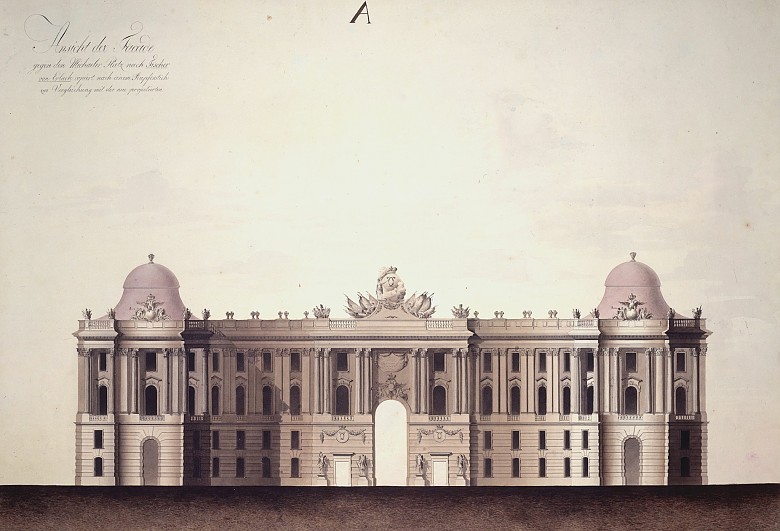

The younger Fischer was also responsible for the design of the Michaelertrakt (St Michael’s Wing, named after the church it faces), whose animated, projecting façade stands in contrast to the old-fashioned restraint of the façades facing the inner courtyard. Forming the main city-side entrance to the Imperial Palace, the structure was originally to have had an open rotunda rather than the cupola that it was eventually given. However, this wing was not completed, remaining a torso until the late nineteenth century. It was Franz Joseph who had it finished in the Baroque style, when the monumental architectural language of the ‘Austrian heroic age’ was once again pressed into service as a symbol of the continuity of Habsburg rule.