The beginnings – the medieval Hofburg

Though its beginnings were as modest as those of the House of Habsburg, over the centuries the Vienna Hofburg developed into one of the great palatial complexes of Europe. The original medieval building, a four-towered fortress surrounded by a moat and outworks, served to strengthen the city fortifications.

The oldest core of the complex is the so-called Schweizerhof, the Swiss Courtyard. This name is not a reference to the Allemanic origins of the Habsburgs but to the Swiss mercenaries who were stationed in Vienna as bodyguard for Emperor Franz Stephan. The institution – comparable to the papal guard – was disbanded after his death, but its name was retained for the innermost courtyard of the palace complex.

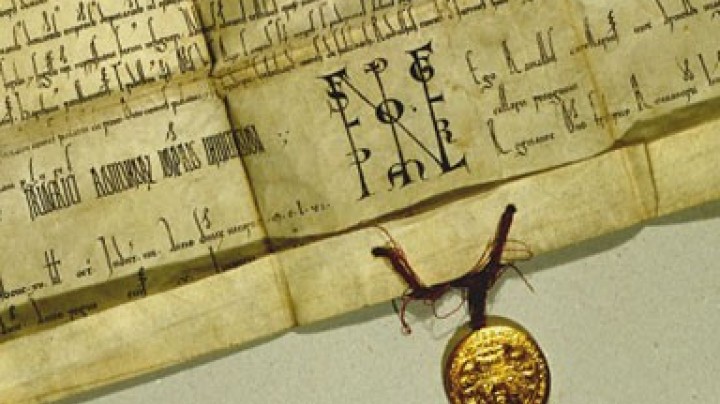

The Hofburg’s precise ‘date of birth’ is a matter of dispute: for a long time the complex was thought to have originated with Ottokar II Přemysl, during whose rule the castle was documented as completed in 1275. However, the latest research has placed the initiative for erecting a citadel on this spot within the context of urban development under the last Babenbergs in the early thirteenth century.

Rudolf I took up quarters here after the Battle on the Marchfeld, though its development as the Habsburg seat of power did not begin until Duke Albrecht II made Vienna his permanent residence in 1339.

In 1458, Frederick III, his brother Albrecht VI and their cousin Duke Sigmund shared rule over the Habsburg domains. This included a share each of the Vienna castle. The problematical situation of living next to one another and the internal family rivalry between the various Habsburg lines were overshadowed by the upheavals of the fifteenth century, de facto precluding the use of the Vienna citadel as a secure and permanent residence. In 1462, Frederick was even besieged in the castle by his brother together with enraged Viennese citizenry; later, his great opponent the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus occupied Vienna, dying there in 1490. Frederick was forced to resort to his residences at Wiener Neustadt, Graz and Linz.

In later times the originally Gothic substance of the building disappeared behind Renaissance and Baroque alterations, which included demolishing or building over the impressive towers. Only traces of the moat have survived.

Nevertheless, the core of the building remained as symbol of Habsburg traditionalism: it was via the inner courtyard, into which coaches were allowed only with special authorisation, that visitors accessed the ceremonial apartments in the Leopoldinischer Trakt (Leopoldine Wing). Thus the Schweizerhof was not only the oldest but also the highest ranking courtyard in the imperial residence.