‘Please wake me tomorrow at half-past three!’

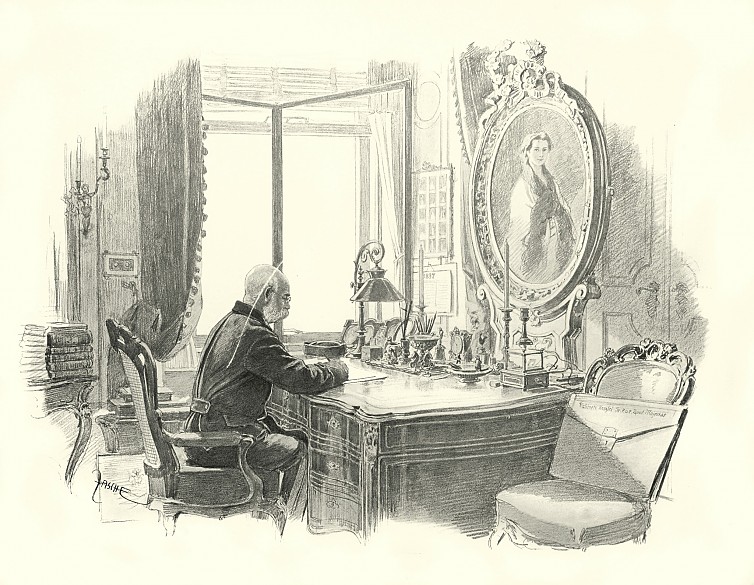

‘Please wake me tomorrow at half-past three’ was Franz Joseph’s instruction to his valet de chambre. He carried out his administrative duties with extraordinary conscientiousness, making himself a model for the bureaucracy in his unquestioning obedience to the state.

Franz Joseph was regarded as an extremely conscientious ruler who adhered to a strict daily routine. As the ‘supreme public servant’ of his state, he embodied an ideal work ethic that expressed itself in precisely planned activities and, above all, punctuality. Even though this ethos had not yet been fully implemented in the civil service, the increased administrative burden – with responsibilities being transferred to district, local and communal authority offices – required fixed hours of work and such virtues as confidentiality and industry.

Professional public service, unlike many other professions, offered a regularized scope of duties. Prescribed working hours, leave regulations, reprimands and a ban on accepting gifts had already been passed into law under Joseph II and were intended to guarantee a stable administrative system. The ‘bureaucratie’ had become an important pillar of the Monarchy. Its task was to uphold law and order. However, paying visits to public authorities on official business became unpopular as this often required a great deal of time and patience from applicants and thus constituted a major obstacle for the Monarchy’s many illiterate citizens.

The regulated training of public servants was intended to put a stop to nepotism and the inheriting of official positions. It was the educated urban middle class who tended to become public servants. This new social stratum weakened the position of the nobility. They formed a ‘second tier of society’ which was defined not only through their profession but also by a way of life appropriate to their station. Higher public servants belonged socially to the upper middle class and therefore had to be accommodated in an appropriate district, preferably in the city centre of Vienna. Their households also required a certain number of servants, for which their salaries were not always sufficient. An aulic councillor, before the 1848 revolution, earned between 1,500 and 3,000 gulden per annum, while a lower level public servant had to make do with 400 gulden. Lower level public servants, therefore, lived mostly in the suburbs of Vienna and frequently had to seek additional paid work. For example, public servants undertook unofficial clerical work at night, and their wives helped out by taking in sewing, since the ethos of their class prohibited wives from working officially.