The ‘Brick Bohemians’ of Wienerberg and imperial building projects

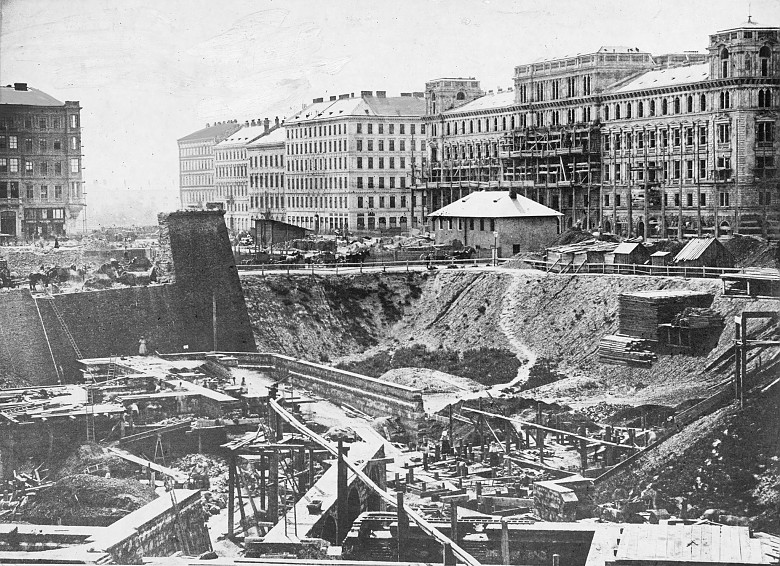

When Emperor Franz Joseph ordered the construction of the Ringstrasse boulevard, a building boom began in Vienna. Architects were commissioned to provide plans for buildings; and to carry out the construction project an army of workers was required. Just for one other major project, the construction of the Arsenal complex, one million bricks were necessary, and these were specially produced in the Wienerberg brickworks.

‘Brick Bohemians’ was the nickname given to the workers from Bohemia and Moravia in the Wienerberg brickworks in the south of Vienna. Although they regarded themselves as being among the more fortunate workers, their working and living conditions were unimaginably dreadful.

In Vienna industrial enterprises preferred to set up in the outer suburbs, where lower rents meant that employees could live near their factories. It was in 1888, in an article published in the Social Democrat journal Gleichheit (Equality) that Viktor Adler first made the public aware of the wretched situation of the brick beaters. Some 3,000 people were accommodated in mass living quarters, which the company made available in return for rent. These were barracks in which men, women and children slept, with between fifty and seventy people in one room. Instead of having their wages paid in money, the workers received tin tokens which they could only redeem in the company canteen. The management exploited its monopoly position and saved money in the food provided for employees, with the result that prices were high and the quality of the food was poor. The long working days (fifteen hours per day, seven days a week) made it impossible to have any other source of income. The wealthy citizens of Vienna did not show much sympathy for the misery of the working masses. Viktor Adler and two brick workers were even fined for distributing their journal without having obtained permission to do so.

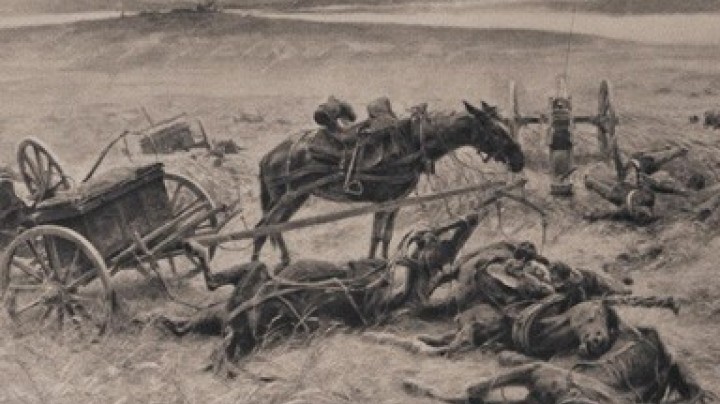

In 1895 the workers, after a bloody strike, were granted not only higher wages but also separate accommodation for families with children, who up to then had also had to live in the mass quarters. The Social Democratic Party declared its solidarity with the brick workers and represented their interests in Parliament. As a result of the workers becoming politically active and of public pressure, the owners of the brickworks had to guarantee them an eleven-hour working day and a work-free Sunday.