With needle and thread – The invention of the sewing machine

Being a skilful inventor does not seem to have brought happiness: one constructor of a sewing-machine died unrecognized and in poverty, while another had his factory completely wrecked.

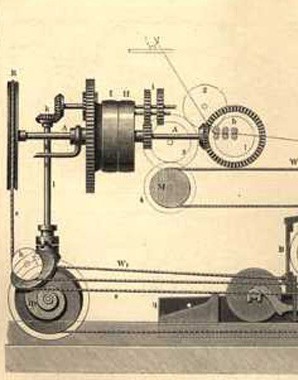

The increased use of workers and machines led to a significant increase in productivity in spinning and weaving in the second half of the eighteenth century. Because the workers doing the sewing could not keep up when it came to the final stages of production, large quantities of fabrics piled up in the workshops. The invention of the sewing machine was, as it were, in the air. Soon patents were registered in France, England and Germany. In the Habsburg Monarchy a tailor called Josef Madersperger had been trying to find a way of speeding up the process of sewing by mechanization since 1800. His first device attempted to imitate a hand sewing. He was granted a privilege – a kind of patent – for this in 1815, but he lacked the financial means needed to turn his invention into a profit-making enterprise and in any case people rejected his machine because they thought that it would rob them of work. Madersperger, who died penniless in a poorhouse in Vienna, has since been regarded as the classic example of the unrecognized Austrian inventor.

Other sewing machines were also relatively unsuccessful at first because they were no quicker than human workers. The process of sewing was not speeded up until the machine invented in 1846 by Elias Howe, an American, helped to bring about a breakthrough in mechanical production. The growth of the ready-made clothing industry also helped to spread the use of the sewing machine. It also meant that middle-class women had to spend less time sewing and thus could devote more time to educating their children and looking after their husbands. For the working classes the sewing machine was a device which their women had to use in order to earn a (low) wage by doing outwork.