If you earn money you can go shopping – The link between the manufactories and consumerism

It was not only for their owners that the manufactories turned out to be veritable ‘gold mines’. The additional income workers earned also boosted trade. But where there was such consumption there was bound to be someone who criticized it.

Quote from the entry on ‘luxury’ in L’EncyclopédieThis is the use that one makes of wealth and industry in order to obtain for oneself a pleasant existence. Luxury has as its principal cause that dissatisfaction with our condition, that wish to be better, which resides, indeed must reside, in all human beings. It is the cause of their passions, their virtues and their vices. (...) Let there be no exclusive privileges any more for certain manufactories and certain types of commerce; let finance not be so lucrative; let burdens and advantages not be heaped so much on the same heads; let idleness be punished by public shame or by removal from office; then you will see – without attacking luxury as such, even without importuning the rich too much – how wealth imperceptibly divides up and increases, how luxury likewise increases and divides up, and everything will return to order.

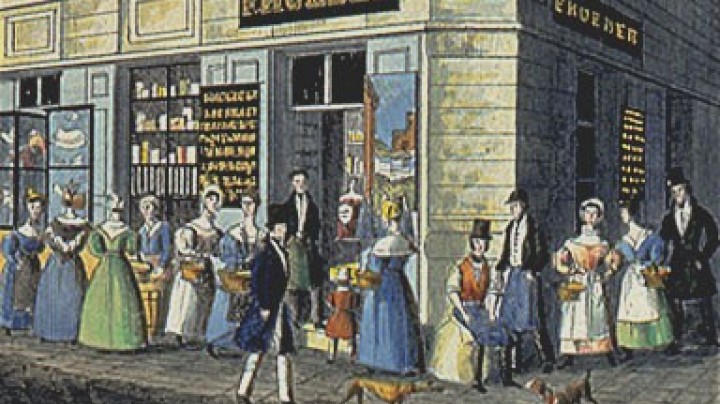

For the rural population, who produced textiles or food above all for their own consumption and for local markets, the manufactories and outwork provided new opportunities to earn money. Women who did outwork made a significant contribution to the increased incomes of households. This additional income meant there was an increased demand for commercial products, which in turn were made in the manufactories. People in the towns were also consuming more, above all the aristocracy with their demand for luxury goods. The goods of which purchases increased included cotton and silk products, clocks, coffee and sugar. After the financial difficulties caused by the Seven Years’ War (1756-63) the imperial Court became active both as a promoter of the manufactories and as a consumer of their products. By granting the so-called ‘factory privileges’ the Habsburg rulers provided the legal basis for the mass production of goods. The entrepreneurs were given a further competitive advantage when the laws regulating where goods could be sold were reformed. Unlike craftsmen, who were allowed to sell their wares only from their workshops or their stalls, the manufactory owners could now sell their products at several locations and outlets.

The new opportunities for consumption soon brought critics on to the scene. These included Denis Diderot, the French writer and one of the authors of the Encyclopédie, who in an essay written in 1772 pondered over a newly acquired consumer product, namely a housecoat, remarking that it had upset his whole household because it did not go with the things he already had. He had merely succumbed to the fashion for making everything new and bright. Be that as it may, in the Encyclopédie Diderot advocated the promotion of ‘luxury’ because this contributed to human ‘happiness’. However, the state ought to ensure that wealth was distributed more evenly. By saying this he was opposing the traditional opinion that ‘luxury’ was a manifestation of extravagance and immorality.