‘I’m a Habsburg – get me out of here!’

The house of Habsburg had no shortage of ‘black sheep’ in the nineteenth century. Some of them found that the family made excessive demands concerning what it regarded as being in keeping with its standing – and bade the imperial house farewell of their own accord.

"In the course of time I have learned to put up with the repeated offences to my person, but my whole life is embittered by the wrongs done to my poor dear innocent Miltschi; I can forgive all those who persecute me, but for the perpetrators of the calumnies spread against my Miltschi I have – and will always have – inextinguishable hatred and contempt."

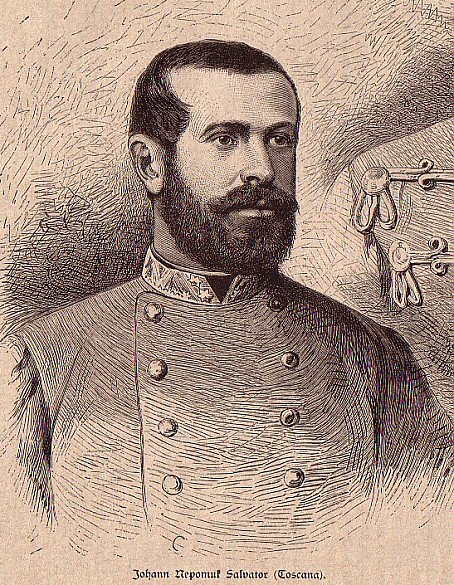

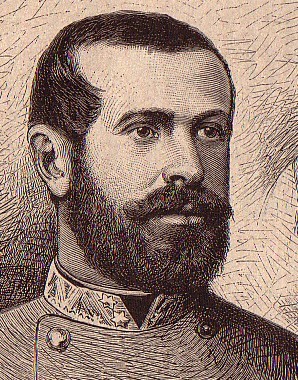

In these lines from a letter to a friend, Johann Nepomuk Salvator described the emotions he experienced during his relationship with the ballet dancer Ludmilla (‘Milli’) Stubel. His relationship with a woman below his station earned him hatred, especially from Archduke Albrecht, the conservative éminence grise of the imperial house. By 1889 Johann had had enough – and of his own free will he renounced membership of the imperial house, taking the name Johann Orth. A little later, he left for a journey to South America on which he was declared missing and from which he never returned.

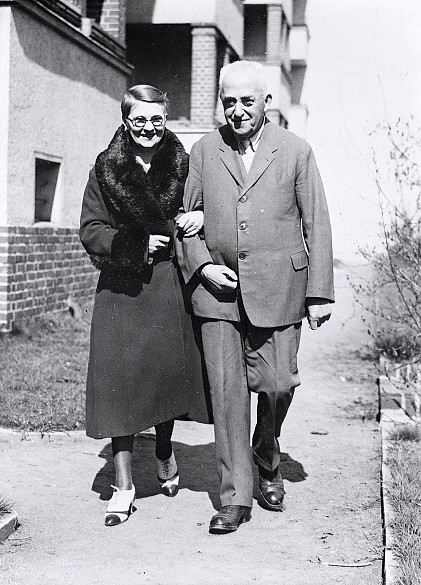

Greater scandal was caused by the case in which Archduke Leopold Ferdinand of the Tuscan line, who was already at loggerheads with the heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand, had made himself unpopular in the archducal house through excessive drinking and womanizing. In December 1902 he finally wrote to the Emperor as follows: ‘I wish to ask Your Majesty’s permission to lay down my rank and title as an archduke and to take the name Leopold Wölfling.’

There were still certain difficulties to be overcome, as Leopold was not willing to go entirely without compensation in renouncing his archducal rights. In his memoirs Als ich Erzherzog war (published in English in 1930 as My Life Story: From Archduke to Grocer) he noted the advantages of the bourgeois life: ‘Having become Leopold Wölfling, I could marry the woman whom I loved madly and live with her in Switzerland as a Swiss citizen.’ His marriage to the woman he loved so madly, the Viennese prostitute Wilhelmine Adamovics, did not last long – in 1907 he divorced her and further relationships followed. A particularly explosive aspect of the Wölfling case lay in the fact Leopold was a friend of the writer and journalist Felix Salten, who was thus enabled to publish reports about the dynastic scandals, including that related to the likewise far from respectable life of Leopold Wölfling’s sister Luise.