The emperor’s furniture – the Hofmobiliendepot

The term ‘kaiserliches Mobiliar’ – imperial movables – evokes the association of exquisite materials, elegant splendour and extravagant abundance. But in order to fulfil these expectations when the emperor actually took his place on his costly throne, a well-oiled administrative apparatus was required in the background.

From the instructions for the k. k. Hofmobilieninspektor (Imperial and Royal Court Movables Inspector) from 1808. Zitiert nach: Hanzl.Wachter, Lieselotte: Eleganz und Geschmack. Sparsamkeit und Tradition. Möbelkunst am Hof Franz’ II. (I.); in: Vernissage 34 (1998) 28–35, hier 28When acquiring new furniture intended for the use of Their Majesties and the older archdukes and archduchesses, attention should be paid not only to good materials and solid workmanship, but also to elegance and taste …, [whereas] in the case of articles … for the younger children of Their Imperial Majesties … [attention should be paid] merely to the two former qualities, without consideration of elegance.

Inventory of a Court officer’s room in the Innsbruck Hofburg from 1856. Zitiert nach: Hanzl-Wachter, Lieselotte: Hofburg zu Innsbruck. Architektur, Möbel, Raumkunst. Repräsentatives Wohnen in den Kaiserappartements von Maria Theresia bis Kaiser Franz Joseph (=Museen des Hofmobiliensdepots 17), Wien u. a. 2004, 31A bed consisting of a wooden frame, 1 straw palliasse, 1 mattress of leather with 16 pounds of cow-hair and 12 pounds of horsehair, a headrest with 3 pounds of horsehair, and a cover of unbleached cloth. Two tables of polished walnut with drawer. A softwood table stained as walnut, with drawer, seven hardwood chairs with leather-covered seats. A softwood sideboard stained as oak. A clothes horse with 6 iron nails. A mirror in a polished frame. A spittoon of polished walnut. Two brass candlesticks. A pair of candle snuffers. Porcelain inkwell with a lacquered tin stand. A stoneware pitcher. A measuring flask. Two drinking glasses. A basin with a lacquered zinc ewer. A porcelain chamber pot. A key to the officers’ room. Ditto for the privy. An iron fire-shovel. An iron poker. An iron stove. Two window curtains of green percale.

Very little permanent furniture was kept in the imperial palaces until the nineteenth century. When the Court changed its place of sojourn, quartermasters were sent ahead to adapt the premises that were to be occupied. Decorators put up tapestries and wall hangings and laid carpets, all of which were regarded as the most precious of fittings that imparted imperial splendour to the suites of spacious rooms. Court ‘harbingers’ were responsible for transporting furniture from one location to the next. The German and French words for furniture – Möbel / meuble – as well as the older English term ‘movable’, still hint at its original ‘mobile’ nature.

Imperial furniture was hence much subject to wear and tear because it was almost permanently on the move, and some items were lost along the way. The first step towards centralizing the administration of court furniture holdings was taken by Maria Theresa when she established the Hofmbolieninspektion or Court Furniture Administration in 1747, in order to gain an overview of the furniture dispersed amongst various locations. This Court department had the task of ensuring the economical and careful use of furniture, of ordering necessary repairs, and of organizing the logistics of transportation.

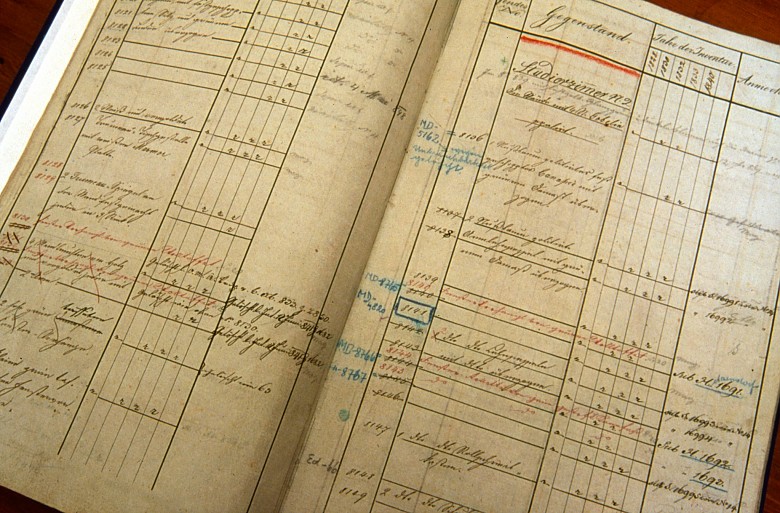

In the nineteenth century it gradually became customary to equip the palaces with permanent furnishings. In the main residences such as the Vienna Hofburg and Schönbrunn Palace Schlosshauptleute (keepers of the palaces) were put in charge of the holdings; at the other imperial residences this task fell to Schlossverwalter (stewards). Detailed inventories were kept to enable constant monitoring of the holdings.

The Hofmobiliendepot was in charge not only of imperial luxury furnishings but also everyday furniture used in the Court buildings; the lodgings of the members of the Court Household and the offices of the Court administration also had to be fitted out. The subtle differences in rank characterizing the Court Household were reflected in the décor of the grace-and-favour apartments. It was not only the quantity of allotted furniture that depended on rank; the quality of its material was also precisely regulated according to service grade. Economy was paramount, and thus many a worn-out or old-fashioned piece made its way down the service grades until eventually it was good only for the scrap heap.

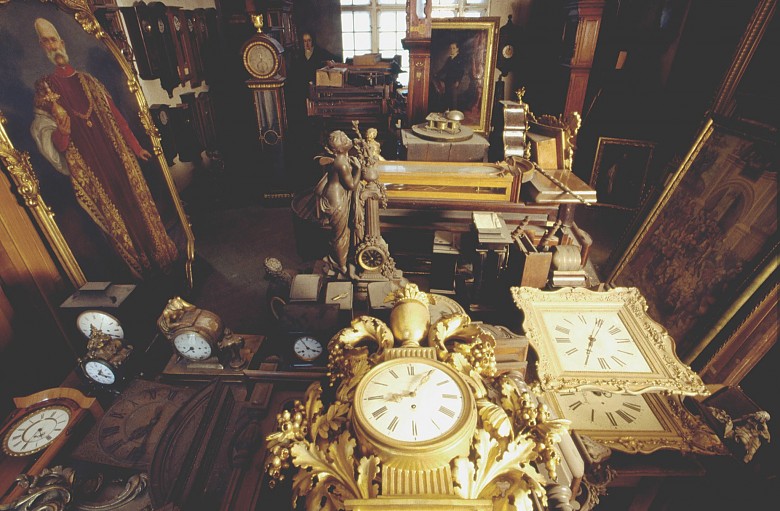

Over the course of the centuries the holdings of furniture, amassed over generations, had grown to huge dimensions. Around 1900, Franz Joseph thus had a building erected on Mariahilfer Strasse, ideally situated between the Hofburg and Schönbrunn, as a central storage facility together with workshops for furniture that was not currently in use – the k. k. Hofmobilien- und Materialdepot, which still exists today. At the same time, a show collection was opened to the public comprising furniture of historical or artistic importance and pieces with special associations that would eventually evolve into the present-day museum of furniture.