The emperor as only one person saw him: the valet de chambre and the human sides of the monarch

Eugen Ketterl was Franz Joseph's last Kammerdiener (valet de chambre). His memoirs, which he wrote after the end of the monarchy, supply interesting insights and quirky anecdotes from the Emperor's everyday life. Ketterl shows the old Emperor and his world bathed in a golden light, viewed through the keyhole.

Franz Joseph to Katharina Schratt concerning the expert dictates of his valet de chambre on matters of fashion.As for the suit, I have to do what Ketterl says; he understands better than I what goes together.

Ketterl on how Franz Joseph behaved towards his staffThe Emperor was very benevolent to all of us and uniquely polite. He never gave orders, he always asked for a service and expressed his thanks when, for instance, he was passed a glass of water.

Ketterl began his career in imperial service as a waiter at the Court table. In 1894, he was appointed to the imperial chamber where, as valet de chambre, he looked after the elderly Franz Joseph's everyday needs until the time of his death.

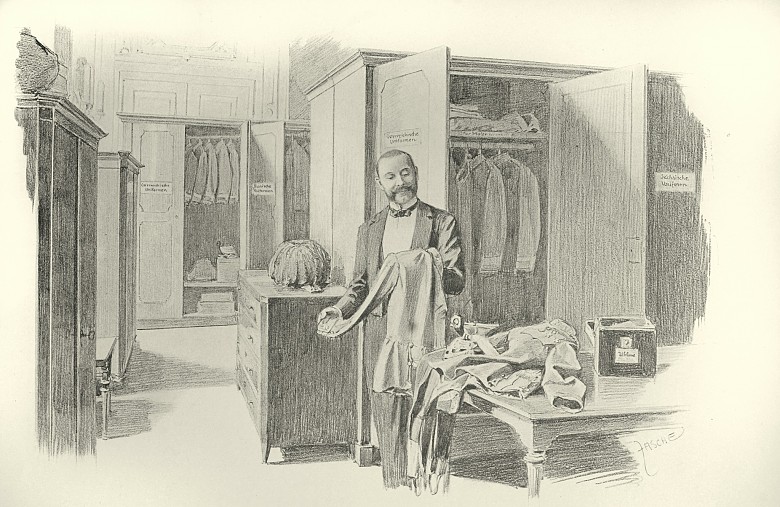

The chamber, of which Ketterl was the head, formed the personal household of the emperor. The chamber staff, who numbered 14, saw to Franz Joseph's personal needs, from ironing laundry to emptying his chamber pot. Besides Ketterl, there were two other valets de chambre, who worked in rotation. Two doorkeepers controlled access to the private rooms, four Büchsenspanner (strictly speaking, attendants who accompanied the Emperor while hunting, and whose duty it was to carry, load and cock his gun) were engaged to provide personal assistance, and two servants and three chambermaids undertook household tasks.

Like that of the emperor, the valet de chambre’s day began very early. At 3.30 am, Ketterl woke the Emperor with the words: ‘Leg mich zu Füßen Eurer Majestät, guten Morgen!’ (‘I fall at your feet, Your Majesty, good morning!’), and assisted the emperor in getting dressed. At 5.00 am, he served breakfast. While the Emperor then dealt with his papers, Ketterl attended to His Majesty’s wardrobe. At 9.00 am, the day’s audiences and meetings with officials began, interrupted by lunch, which Ketterl had to serve at the emperor's desk. In the evening, the valet de chambre prepared the Emperor's wardrobe for receptions. When the Emperor went to bed, he helped him with his evening ablutions.

As for the Emperor's personal lifestyle, Ketterl stresses his modest needs. His household effects were of the robust, utilitarian sort, the technical equipment outdated, and there were no modern facilities installed. He had a predilection for uniforms, but paid little attention to elegant civilian dress, and so the imperial wardrobe was extremely modest in scope. Ketterl made a cautious attempt at modernizing the household; the imperial wardrobe was updated and the installation of technical innovations such as a telephone and WC was instigated, although the Emperor took a sceptical view of such changes.

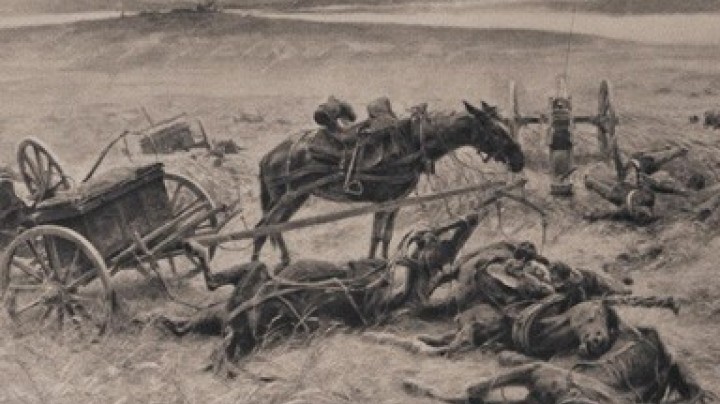

Ketterl also discreetly expressed his view on the weaknesses and human sides of the Emperor, such as his cigar smoking and his association with Katharina Schratt. He describes the growing isolation of the ageing Emperor within the family, but also Franz Joseph’s inner distance from the modern world outside the imperial court, which had become a relic of an age long past.