Who am I?

Jupiter, Saturn or the Holy Family? The Habsburgs’ gallery of ancestors extended back – depending on current political needs – from Charlemagne and the Merovingians to Isis and Osiris, not forgetting Hercules, Noah and Adam.

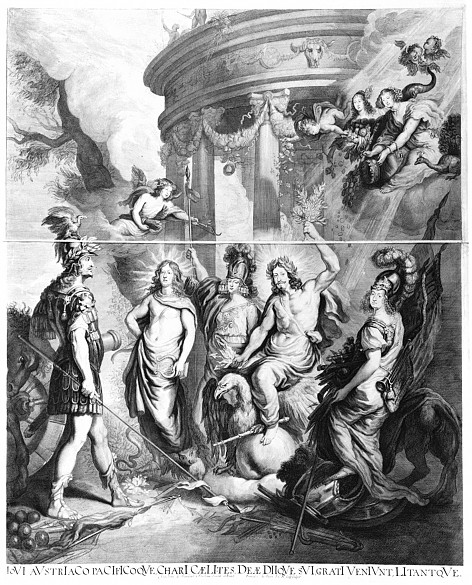

The commission for this family portrait, which survives only in the form of an engraving by Franz van der Steen, was awarded to the painter Joachim von Sandrart in 1653. The concept of the painting, in which the imperial family assumes the role of the Olympian family of gods, came from Emperor Ferdinand III himself.The Emperor appears as Jupiter, seated on an eagle, on the ground, [in] his right hand an olive branch, in his left his thunderbolt, and crowned with laurels, thus might my portrait be rendered. From the skies the two deceased Empresses as Juno and Ceres, the one offering him riches, the other fruitfulness. The Queen from Spain as Minerva, presenting armour and art. Bellona, the present Roman Empress, casting military instrumenta at his feet. Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in the shape of Mars, also offering instrumenta bellica. The Roman King in the shape of Apollo, with musical instruments. My little son in the shape of Cupid, but clothed, presenting quiver and bow.

Emperor Maximilian I pursued the dynastic programme of including all the rulers of the Western world in his lineage. He also sought to prove his descent from saints, to document how God had chosen the House of Habsburg. He thus commissioned extensive genealogical investigations intended to secure him claims to as many European dominions as possible, in case a ruling house died out. He also exploited the arts to serve his genealogical programme.

Maximilian’s court painter Bernhard Strigel created an early and rare example of a portrait of a ruler and his family which also includes deceased members of the family, that is, a constellation of individuals who never met in real life. Inscriptions in the painting suggest that the imperial family is descended from the Holy Kinship. Until the reign of Maria Theresa, depictions of Habsburg rulers were mostly limited to individual portraits or likenesses of emperors and their consorts; family depictions constituted the exception.

Paintings that represented the Habsburgs as saints or Biblical figures were also popular. Frederick III, Maximilian I and Charles V had themselves painted as one of the Three Wise Men, Joseph II as David, and Karl I – after his abdication – was even shown as Christ. Biblical motifs were also popular among the Habsburg women: for example, Maria Theresa and her infant son Joseph (later Joseph II) were portrayed as Madonna and Child.

Depending on the prevailing political interests, different ancestors were given prominence. Around 1300 the Trojans were ‘discovered’ as predecessors; Maximilian I lighted on this, tracing the dynasty back to Jupiter and Saturn. This ‘branch’ of the ancestral lineage was revived during the Baroque era as a welcome source to draw on for staging courtly displays.

From the middle of the seventeenth century it seemed opportune to emphasize the connection with the House of Lorraine, which was to play such an important role in dynastic politics during the eighteenth century. In this interpretation the marriage of Maria Theresa and Franz Stephan of Lorraine united two branches of a single dynasty, thus founding a new house and compensating for the dying out of the male Habsburg line with the death of Charles VI.