A medieval ‘freelancer’: Albrecht Dürer

He worked for courts and cities and fought for recognition for his profession: Albrecht Dürer’s (1471–1528) biography provides a classic account of an artist’s life around 1500.

Letter from Maximilian I to the Council of Nuremberg dated 12 December 1512As Dürer had proved himself and was a respected artist, we have through this been moved to favour him with especial support, and thus desire you earnestly in our honour to exempt the said Dürer, in keeping with your laws, from additional imposts, taxes and other dues, in testimony of our friendship for him and for the sake of the marvellous art of which it is but just that he should freely benefit. We trust that you will not refuse the demand we now make of you, because it is proper, as far as possible, to encourage the arts he cultivates and so largely develops among you.

Albrecht Dürer was a native of Nuremberg, where he completed an apprenticeship as a goldsmith in his father’s workshop. He then trained as a painter and copperplate engraver. In 1490 Dürer took to the road, as was then customary for journeymen, travelling around Germany and also to Italy, where he studied Venetian painting. On the journey there and back he painted and drew landscapes from nature, one of the first German artists to do so. His nature studies such as the Young Hare are today famous all over the world.

In 1497 he set up as an independent artist-craftsman in Nuremberg, establishing his own studio a little later in which he painted portraits, self-portraits and produced copperplate engravings and woodcuts. Dürer raised the copperplate engraving and woodcut to the status of works of art in their own right, independent of book illustration. He was adept at exploiting the advantages of print-making in that it allowed him to popularize his oeuvre at low cost and also represented a secure source of income. He distributed his prints himself or via bookshops.

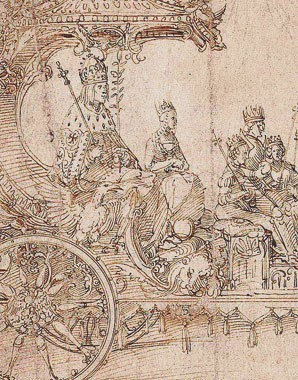

From 1512 Dürer executed several commissions for Emperor Maximilian I, for example the studies for a triumphal car for the monumental work Triumphzug.

Maximilian granted him an imperial patent to protect his woodcuts and copperplate engravings from being copied, thus making his works recognizable as ‘genuine Dürers’ and ‘trademark goods’. The emperor, who had a high estimation of the artist, persuaded Nuremberg Council to grant him exemption from taxes.Maximilian subsequently granted him an annuity of 100 gulden. After the emperor’s death the artist travelled to the Netherlands in 1520 on the occasion of the coronation of Charles V to request that this annuity be continued. He was acclaimed by princes, scholars and artist in the Netherlands, and even received an offer to remain in Antwerp for an annual salary of 300 gulden and a house.

However, Dürer elected to return to Nuremberg, and in his old age occupied himself with the study of the theory of art, in particular the laws of proportion. In 1525 he published his Underweysung der Messung, postulating the intellectual nature of art, for which he sought to set up rules. The artist fought for the recognition of the fine arts as a branch of the liberal arts (the seven liberal arts of rhetoric, grammar, dialectics, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy and music) based on the model of Italy, where the fine arts enjoyed greater recognition. Dürer died from malaria in 1528, aged only fifty-six.