Syphilis – an American disease?

Syphilis spread like an epidemic in early modern times. But what had triggered it?

Another new and widely feared disease was syphilis. In 1493 it first occurred in Spanish trading towns. However, there was some dispute as to how it was transmitted; while the miasma theory traced its outbreak back to particular constellations of the planets, Paracelsus suspected it resulted from a promiscuous lifestyle, for which God punished the perpetrator with syphilis. Another widely held explanation was the so-called Columbus theory, which counted syphilis among the diseases typically contracted by sailors. Columbus had brought the disease from the New World to Spain, from where it spread to Naples. During the French-Italian war it was rampant among the troops of mercenaries and killed thousands in Europe. In an edict published in 1495, Emperor Maximilian I confirmed that such a disease had never been observed before. Although theories differed with regard to the way it was spread, the notion of a venereal disease transmitted via sexual intercourse soon prevailed.

As a consequence, nudity and sexual permissiveness were henceforth to be heavily restricted, and theologians warned people against a life of promiscuity and sin. Sexual intercourse before and outside marriage now increasingly became the focus of legislation. Visits to the bath house were now regarded as morally dubious, causing the barber-surgeons who ran them to lose much of their former prestige, and new ideals of propriety, modesty and restraint emerged. Thus, contracting syphilis became an ‘embarrassing’ matter which was often kept secret by those who were suffering from it.

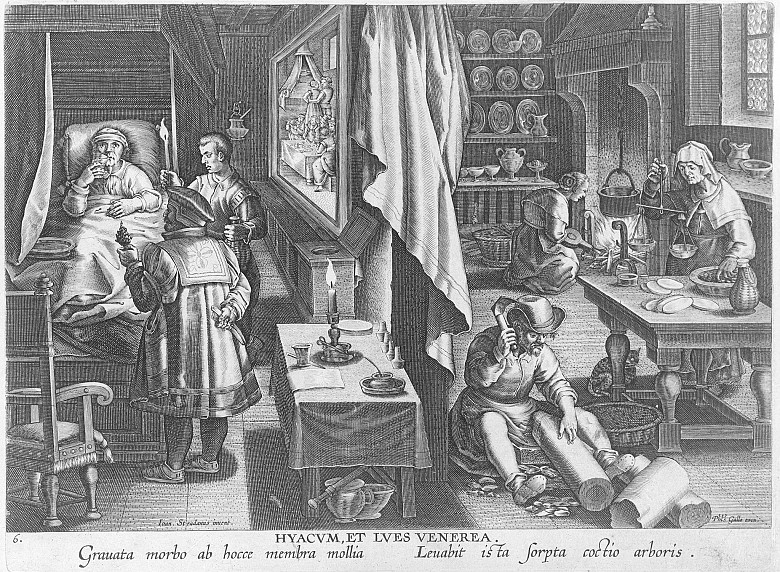

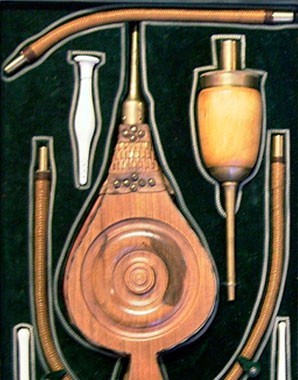

Remedies for syphilis abounded and became almost as numerous as theories as to its origin. Until the nineteenth century, for instance, people tried to cure it using mercury, and during the sixteenth century they boiled the wood of the tropical American guaiac tree to treat the disease.