Life in the towns and cities

Stadtluft macht frei (‘city air sets you free’) was a widespread saying in the German-speaking lands of the Middle Ages. Urban artisans, tradespeople and merchants led relatively autonomous lives until early modern times. However, when Vienna became the imperial residence things changed …

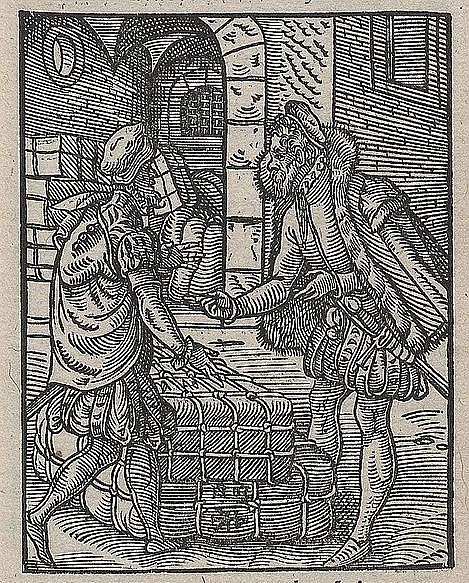

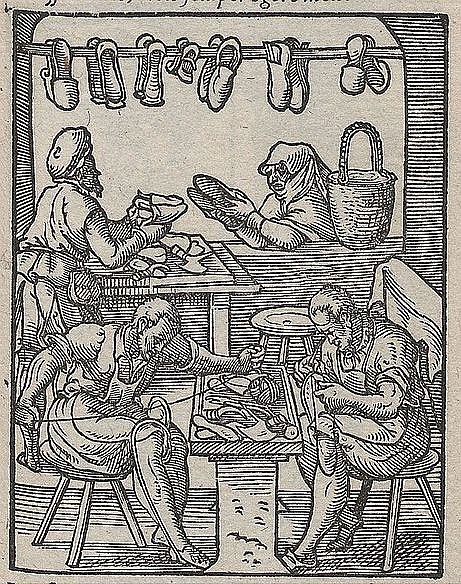

In the early modern era, towns and cities were dominated by craft and trade. Although the city dwellers did not constitute an estate in their own right, they were able to lead relatively autonomous lives, independent of the local ruler’s court. The citizens of a town belonged to rigidly defined social classes, and only very few of them possessed civic rights. For instance, only someone who owned a house had full rights. Most of the citizenry were craftsmen, who were organized in guilds.

Ferdinand I’s bestowal of a new regime on Vienna 1526, which soon afterwards became the dynasty’s permanent residence, was intended not only as an assertion of absolutist principles but also as a way of putting the city directly under the sovereign’s control (Wiener Neustädter Blutgericht).

The old privileges of the craftsmen, who had actually made Vienna into the important trading centre that it was, were revoked. A central government soon turned the city into a royal administrative and commercial centre which was now dependent upon the Court. In the city councils, aristocrats who had pledged allegiance to the sovereign took the place of tradespeople and merchants, thus swiftly suppressing any say the citizens had in the political process.

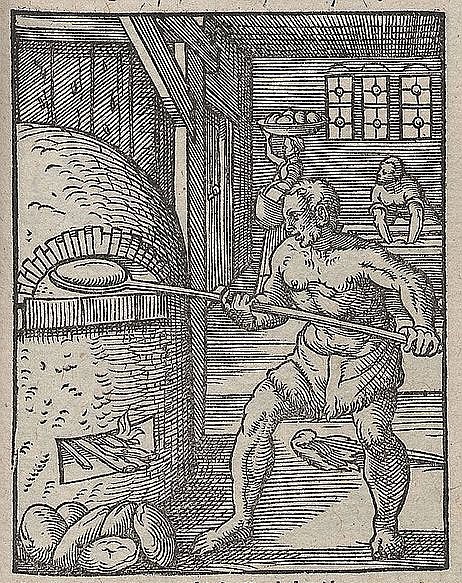

The economic circumstances of many tradespeople deteriorated due to competition from Court artisans, who were permitted to employ tailors, goldsmiths, wig-makers and so on as they were exempt from the guild regulations. These craftsmen worked not only for the Court itself but also for the well-to-do citizens who strove to emulate the aristocratic way of life. Small traders also had to compete with members of the Stadtguardia (city militia), who had been responsible for law and order in many towns following the Turkish Wars but whose pay was so meagre that they had to resort to other activities to supplement their income, working as bakers, cobblers or innkeepers. In addition there were the so-called Störer (lit.: ‘trouble-makers’, in the sense of moonlighters): often non-guild craftsmen who rarely had the title of a master craftsman, these ‘artisans without a workshop’ worked in the homes of their clients. Tailors in particular frequently worked in this way.

The imperial capital attracted nobility and the higher clergy alike, creating the ‘district of the gentry’ (Herrenviertel) around the Court. As the Church was claiming additional premises for their monastic orders, many wealthy middle-class citizens had to vacate their homes. Aristocrats, Court staff and public servants were accommodated tax-free in special houses. House-owning citizens were obliged to put a part of their dwellings at the disposal of Court personnel.

These changes affected the social life of the merchants, who strove to improve their social standing or even set their sights on a title, a prime example being the Fugger dynasty.