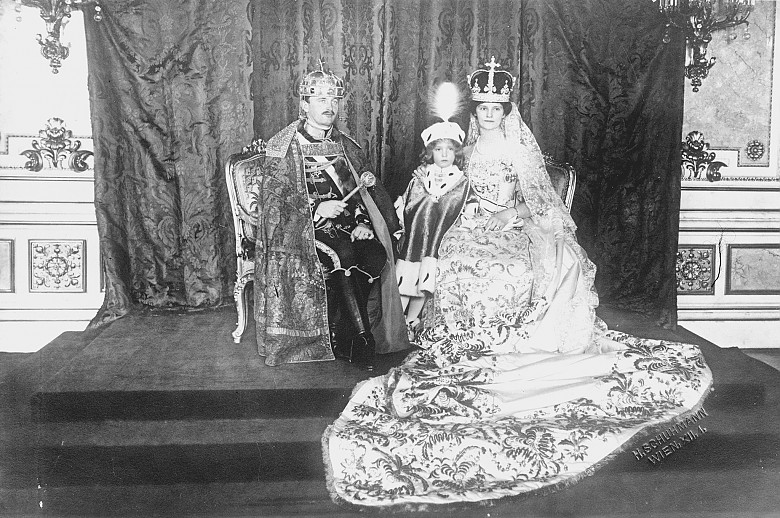

Karl as heir to the throne and monarch

After the assassination at Sarajevo, in which the heir apparent Franz Ferdinand was killed, Karl became first in line to the throne sooner than expected.

Following the outbreak of the First World War Karl was seconded to Field Army Command, which was led by Archduke Friedrich and located in Teschen (Cieszyn) in Silesia. Later, promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Field-Marshal (equivalent to Major-General), he participated in offensives at the front in Galicia, where he witnessed the growing military exhaustion of the Imperial and Royal Army. This experience fuelled his conviction that to persist in fighting the war on the side of the German Empire would lead to the downfall of the monarchy.

Following the death of Emperor Franz Joseph in November 1916 Karl ascended the throne at the age of 29. Confronted with the burning issues of the weakened monarchy, Karl soon showed that he was inadequately prepared for his role as ruler. He was keen to distinguish himself as a modern monarch and ‘people’s emperor’, but overestimated his capabilities. His actions were characterized by overzealousness and a lack of perspective. Sudden changes of course and contradictory, unconsidered decrees earned him the epithet of ‘Karl the Sudden’.

Biographers unanimously describe the young monarch as person of integrity with good intentions. Nonetheless his image of himself as ruler was obscured by his excessive sense of mission and an unshakable attachment to legitimist ideas. His honest (albeit often enough naive) efforts to implement reforms foundered on political reality and the juggernaut of war.

Karl assumed personal command of the armed forces, moved the military command centre to Baden near Vienna and dismissed the powerful chief of staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf. By re-convening Parliament – on the outbreak of war Parliament had been prorogued and the country ruled by decree, thus turning the Austrian half of the empire de facto into a military dictatorship – he ended the army’s rule over civil affairs of state.

In Hungary Karl’s room for manoeuvre to implement sweeping reforms had been severely limited by his hasty coronation which had entailed swearing an oath on the existing constitution.

Alarmed by the events of the Russian Revolution, Karl pressed for the dissolution of the alliance with Germany and the conclusion of a separate peace in an attempt to save the Monarchy from imminent collapse. At the end of 1916 he entered into secret negotiations with France, using one of his wife’s brothers, Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, as go-between. When the secret papers relating to this venture, whose existence Karl had previously denied, were published in April 1918 due to indiscretions and diplomatic mishaps (revelations known as the Sixtus Affair), the emperor’s credibility at home and abroad was completely destroyed.

As a consequence, Austria-Hungary lost the last remnants of its independence to manoeuvre and was forced enter into even closer ties with Germany. Emperor Karl was fatally compromised as a decision maker and politically disempowered.

This also exposed the inner disunity of the Monarchy: the German Nationalists, whose strength was growing, regarded the dynasty and above all Karl’s wife Zita as traitors and demanded unconditional adherence or ‘Nibelungentreue’ to the alliance with Germany (‘Nibelungentreue’, lit. ‘Nibelung loyalty’ – an expression coined by the German Chancellor Prince Bernhard von Bülow in a speech to the Reichstag on 29 March 1909. Bülow used it to underline the loyalty of the allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary, to each other. The pretentious phrase caught on in the newspapers and was derided by the Austrian satirist Karl Kraus. Nowadays it has come to denote blind unquestioning loyalty, even to one’s own detriment). The other nationalities began to seek their future in autonomy and were encouraged in this by the Western powers, as by the spring of 1918 the break-up of the Monarchy had become one of the war’s principal objectives.