Joseph I: the Austrian ‘Sun Emperor’

Austria’s newly won status as a Great Power now had to be demonstrated in a striking manner. Joseph, who represented the Habsburg answer to the French Sun King Louis IV, was to be stylized as the Austrian ‘Sun Emperor’.

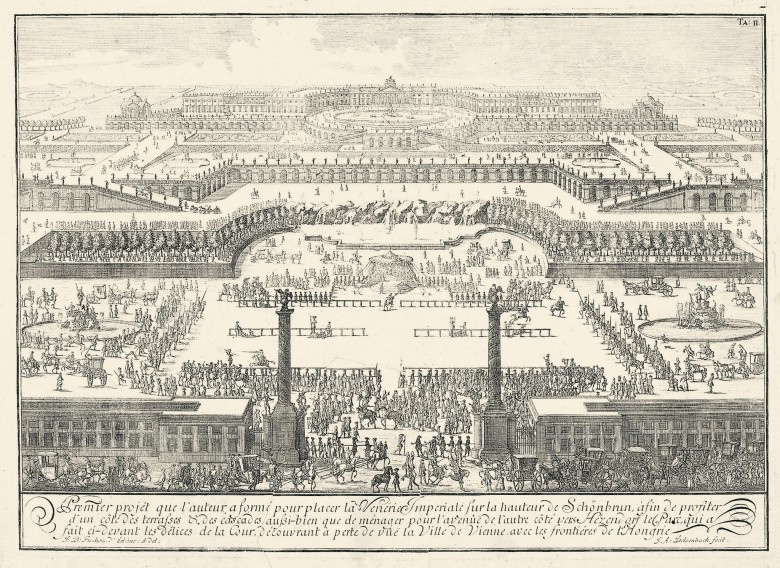

At the court in Vienna new ways were sought of expressing the Habsburg claim to imperial power in art and propaganda. It is against this background that the spectacular ‘First Project’ for a palace at Schönbrunn should be seen. Drawn up by the imperial court architect Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, this megalomaniac design was not so much a set of actual plans for the construction of a palace as a skilful representation of Habsburg fantasies of omnipotence expressed in Baroque architectural language.

A fresh wind was blowing at the otherwise rather staid Vienna Hofburg. Crown Prince Joseph was surrounded by a circle of individuals known as the ‘Junger Hof’ (lit. ‘Young Court’), the future leading figures of government, among whom the most famous was Prince Eugene of Savoy. This extraordinary military genius also played a part in bringing western European Enlightenment ideas to Vienna.

The War of the Spanish Succession dominated the political focus of the Viennese court in the years around 1700. The Austrian branch of the Habsburgs had hopes of assuming the inheritance of the Spanish branch of the dynasty. Although the latter’s global empire was a mere shadow of its former importance, and its last Habsburg ruler, Charles II, had suffered badly from the effects of generations of interbreeding in the family, the Spanish crown was still considered one of the noblest in Europe, and the Vienna Habsburgs dreamed of uniting the two lines.

Joseph’s younger brother Charles (later Charles VI) was sent to Spain as pretender to the throne. The plan was for Charles to found a new Habsburg line in Spain. This took place with the agreement of Austria’s allies, Britain and Holland, who were demanding that the Spanish inheritance be divided in order to preserve the balance of power in Europe. However, the Habsburg claim was contested, and a lengthy and costly war between the Great Powers of Europe ensued, affecting large parts of the continent.

The ruling emperor Leopold and his crown prince Joseph also hoped to gain territory in Italy, planning an expansion of Habsburg dominion under the guise of imperial authority. The ruler of the Holy Roman Empire was once again to become the leading power in the Apennine Peninsula.

In 1705 Emperor Leopold died and his son assumed the regency. Joseph developed a strong sense of dynastic destiny and began to cherish some partly rather exaggerated ideas. The Viennese court saw in Prince Eugene’s military successes against the French the basis for challenging the Sun king’s hegemony. By concentrating on strengthening his position in the Empire and achieving a greater hold over the princes of the Empire Joseph sought to position the Holy Roman Empire as a Habsburg counterpart to France.

As ruler of the Habsburg Monarchy he started off promisingly, introducing a programme of reforms aimed at unifying the heterogeneous lands of the Habsburg dominions. Many of the projected reforms were however never implemented, as Austria’s changing fortunes in the War of the Spanish Succession tied up all her resources.

In the meantime the situation had become more complicated: Joseph’s fledgling rule had been weakened by an uprising of the Hungarian nobles, called the Rákóczi Uprising after its leader. The Hungarian magnate Francis II Rákóczi spearheaded a war of independence (as the Hungarians saw it) against the excessively strict rule of the Habsburg court, which wanted to bind Hungary – only latterly freed from Turkish dominion – closely to Vienna and had begun to carry out political and administrative reorganisation on strictly absolutist principles.

This meant a war on two fronts, since troops were needed to quell the uprising that were then lacking on the western front. The Hungarian rebels were extremely successful, bringing broad swathes of the country under their control. The rebel forces, known as kuruc, made plundering incursions into the border areas of Austria, Styria and Moravia. In 1707 at the Diet in Ónod the rebel nobles declared Joseph’s deposition as king of Hungary. It was not until after Joseph’s death that Charles managed to end the uprising by making concessions at the Peace of Szatmár in 1711 and to bind Hungary more closely to the Habsburgs.

With the emperor’s sudden death from smallpox at the age of only thirty-three in 1711 the Monarchy had lost a major repository of its hopes for the future. The Habsburg scheme to become a Great Power was plunged into crisis. Joseph’s brother Charles was now the only surviving male Habsburg and his successor as Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Austrian Monarchy. Charles was still an aspirant to the Spanish throne, and Britain, which was allied to Austria, considered this to constitute too great a concentration of power in one hand. In order to preserve the balance of power in Europe Charles was forced to relinquish his claim to the Spanish throne. The great dream of restoring Habsburg rule in Spain was finally at an end.

Because of the brief duration of his reign Joseph I is not generally very well known and is sometimes referred to as the ‘forgotten Habsburg’ on the imperial throne.