Frederick V, IV and III

Frederick, the fifth monarch to bear this name in the House of Habsburg, was the fourth Frederick to bear the title of Roman-German king and the third Frederick to reign as emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1440 Frederick was elected Roman-German king by the prince-electors of the Empire. The coronation did not take place until 1442, as Frederick first had to secure his authority in the Austrian lands as tutelary regent for Ladislaus, who was still a minor. The Styrian Estates were refusing to recognize Frederick as regent. His authority within his immediate family was also being questioned: his younger brother Albrecht (Albrecht VI in the dynastic numeration) was making forceful demands for his share of the inheritance.

Thus Frederick was confronted with a number of conflicts. Always the pragmatist, he realized that he lacked the power to implement his schemes. He avoided direct confrontation, trusting in his negotiating skills and tenacity. His strategy was to keep conflicts that he was unable resolve by force hanging in the balance and to let time work for him.

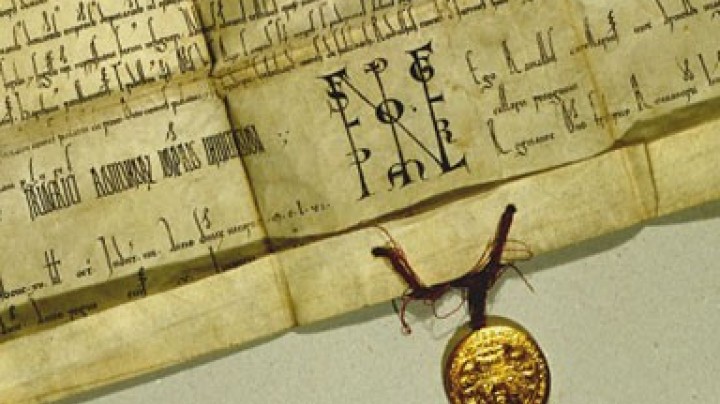

Within the Holy Roman Empire he was a weak monarch, dispensing with grand gestures in the face of the many interests that opposed him. Instead he concluded a series of frequently changing alliances. His most important act as head of the Empire for his own dynasty was to confirm the Privilegium Maius, the notorious forgery perpetrated by his ambitious forebear Duke Rudolf IV, whose visionary schemes Frederick greatly admired. Henceforth the Habsburgs were now officially permitted to bear the unique title of archduke.

Frederick was also the only Habsburg to be crowned emperor in keeping with medieval tradition by the pope in Rome. The coronation took place in 1452 and was to be the last of its kind in the history of the Holy Roman Empire. Frederick exploited a favourable opportunity for his journey to Rome, as Pope Eugene IV and the latter’s successor Nicholas V were indebted to him for their election and for the ending of the papal schism at the Council of Basle. His coronation at Rome represented a great moment in Frederick’s life, one of his rare triumphs. His wedding to Princess Eleonora of Portugal also took place in Rome on this occasion.

In meantime, however, the situation in the Austrian patrimonial lands had escalated. The Lower Austrian Estates revoked their fealty to Frederick and laid siege to the newly crowned emperor in Wiener Neustadt shortly after his return from Rome. The Lower Austrian nobles were demanding the release of Frederick’s ward Ladislaus, who was the only candidate the Estates were prepared to accept as their sovereign. In Ladislaus Frederick lost his greatest trump card in his bid for power and sovereignty in Austria. The Emperor was limited to his ancestral dominions of Inner Austria, which considerably restricted his sphere of action.

Here too Frederick was confronted with problems, namely the aftermath of the conflict-laden relations between his father, Duke Ernst, and the imperial Luxembourg dynasty. In order to undermine Habsburg positions in their ancestral lands Emperor Sigismund had raised the Counts of Cilli, a family whose ancestral possessions lay on the borders between Styria and Carniola, to the rank of princes of the Empire, thus removing them from the Habsburg sphere of influence. The result was a long-drawn-out conflict over sovereign rights. Frederick eventually gained the upper hand purely by chance, when Ulrich of Cilli, his ambitious adversary, was assassinated in 1457 and Frederick was able to seize his possessions.

His ward Ladislaus Postumus also died in 1457 at the age of seventeen. Frederick was now sole heir to the Austrian lands. However, through his ward’s death he had lost an important pawn in his bid for power in Bohemia and Hungary. In both kingdoms the Estates elected national candidates for the throne: George of Poděbrady in Bohemia and Matthias Corvinus in Hungary.