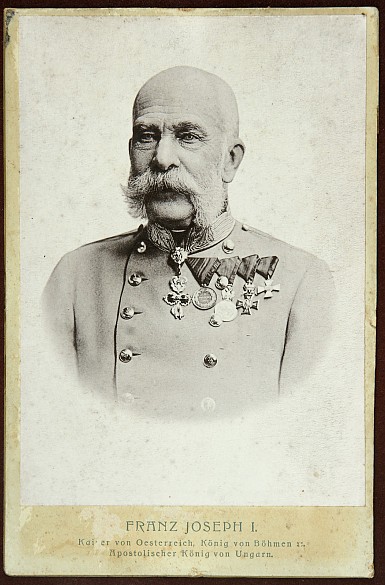

Franz Joseph: The very model of an emperor

Emperor Franz Joseph reigned for 68 years, the longest of all the Habsburg rulers. He was a symbol of integration, and when he died the Habsburg Monarchy lost one of its most important pillars.

Franz Joseph looms large in the historical consciousness of posterity. Towards the end of his life he became a semi-mythical figure, a symbol of the Monarchy who was beyond criticism. Even today, Franz Joseph is regarded as the very epitome of the emperor in the successor states of the Monarchy.

His personality developed in unique and difficult circumstances: from his earliest youth it was impressed up on him that he had been chosen as emperor, an office that was to be served with humility. His mental isolation was reinforced by court ceremonial, which elevated his imperial majesty to an almost religious level. Franz Joseph was wholly imbued with the concept of his divine mission as emperor.

As a young man Franz Joseph was described as charming, courteous and good-looking. With the passing of the years he became taciturn and withdrawn, letting few of his emotions show. He strove to preserve a measure of distance between himself and the people around him, both as monarch and in the family. He had a patriarchal understanding of family and was the undisputed head of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, brooking no opposition to his ‘supreme will’, which in extreme cases could lead to exclusion from the family and the loss of title and privileges. Franz Joseph was an authoritarian father figure, a side that became especially evident in the tragic fate of his son Rudolf: the emperor reacted to his son’s liberal ideas with a complete lack of understanding, and found his subsequent suicide wholly incomprehensible.

No great thinker, Franz Joseph was a dry pragmatician who dismissed the philosophizing views of his wife as ‘cloud-clambering’. While the emperor was in principle interested in painting and architecture, he had developed very conservative tastes – the Viennese Modern Movement, today celebrated virtually as the trademark of Viennese cultural life in the period around 1900, remained foreign to him. The love of music that had otherwise been strongly represented in the dynasty was not shared by Franz Joseph. He attended social events mostly out of a sense of duty but disliked them intensely.

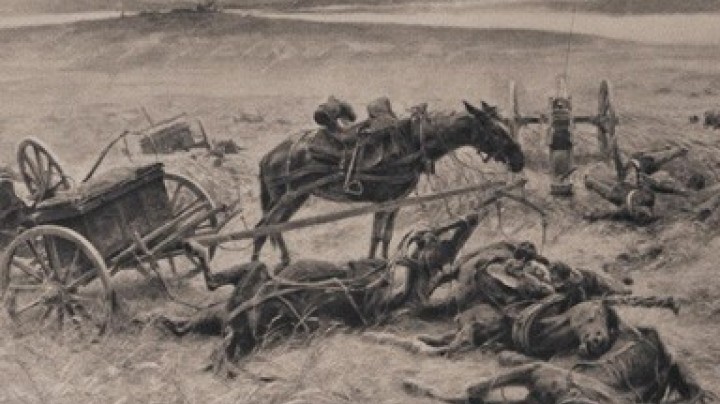

Franz Joseph’s militaristic upbringing had left its mark on his personality. Mocked as the ‘red-trousered lieutenant’ on account of his passion for all things military in his youth, he regarded the army as the most important pillar of the Monarchy, despite the fact that he was not blessed with any aptitude for strategy. Franz Joseph was an officer more suited to peacetime, a stickler for order with a marked enthusiasm for military exercises and parades. This also manifested itself in his love of military uniform, which became his preferred daily attire.

The emperor’s personality is described by all sources as sober and unimaginative: aware of his obligations to the point of pedantry, he considered punctuality and orderliness to be the highest virtues. Franz Joseph was a bureaucrat who was capable of processing immense quantities of work and adhered to a strict routine, developing ‘… an almost religious belief in the value of bureaucracy’ (Holler). However, he found himself overwhelmed by the flood of files, getting bogged down in minor details, and was incapable of delegating even the smallest matters. Moreover he could be indecisive at times, demanding yet more expert reports and information, which led to further delays in the decision-making process.

Franz Joseph escaped from his ‘paper existence’ as he called it during his summer retreat to the Salzkammergut, which became a kind of spiritual home for him. The emperor spent several weeks each summer in his ‘beloved Ischl’, where, attired in traditional Austrian hunting dress, he would relax by engaging in his favourite pastime of shooting.

As far as his lifestyle was concerned, Franz Joseph was very modest in his demands: the décor of his private apartments and his culinary predilections reveal him to have been a person of very average tastes. In the first decades of his reign he was also straitened by financial circumstances, as although his uncle Ferdinand had abdicated he had not waived his right to the family fortune, with the result that Franz Joseph was dependent on the comparatively modest appanage he received from state funds. For larger-scale expenditure he had to ask for help from his uncle in Prague. Even Elisabeth’s wedding jewellery was paid for by Ferdinand. It was not until the death of his uncle in 1875 that Franz Joseph had Ferdinand’s large private fortune at his disposal, a circumstance that immediately manifested itself in a huge rise in expenditure for his wife Elisabeth, whose extravagant wishes he was now able to fulfil more easily. Although he developed an almost compulsive frugality as far as expenditure on his own person was concerned, he was all the more generous towards those who were important to him, such as his wife or his companion Katharina Schratt. Franz Joseph funded the exclusive lifestyles of these two women, viewing their extravagance with incomprehension yet acquiescing to it with little protest.

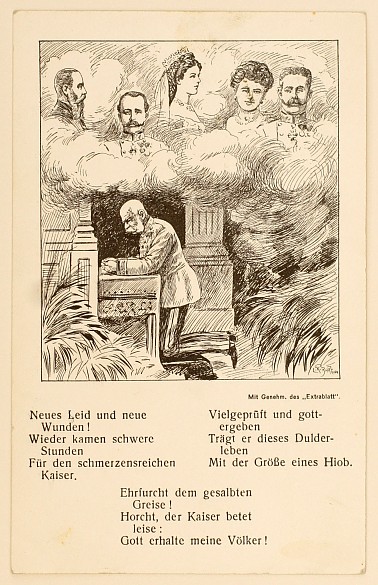

A person of integrity and decency, Franz Joseph was variously described by people around him as stoic or even unfeeling in his reaction to the numerous political and military defeats he suffered as ruler, which he took as personal setbacks. He overcame several tragedies in the family with the same composure, including the early death of his first child Sophie, the execution of his brother Maximilian, the failed emperor of Mexico, the suicide of his only son Rudolf and the assassination of his beloved Sisi. All this fostered the image of the emperor ‘who was spared nothing’, as a tower of strength, who remained unbowed despite repeated blows of fate.

Towards the end of his life Franz Joseph became a relict of a time long past, increasingly isolated from the developments taking place in contemporary society. He came to symbolize the latter years of the Habsburg Monarchy, which would probably have needed a more farsighted and open-minded monarch to master the problems that needed to be dealt with. With his rigid traditionalism the ‘old gentleman in Schönbrunn’ thus contributed to the decline of the Monarchy against his own best intentions.