Franz Joseph as ruler – Part One: 1848-1867

Revolution and reaction: the young emperor and Austria’s path to neo-absolutism.

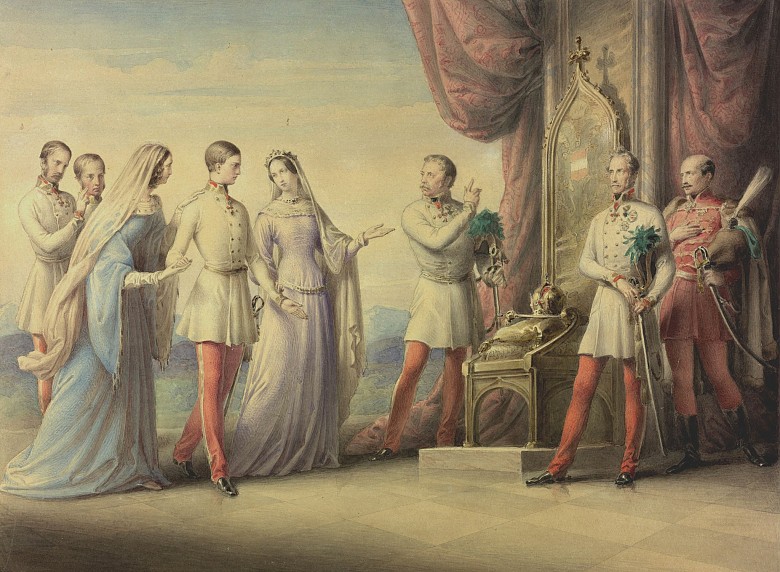

The results of all the efforts that had been invested in grooming the archduke as a future monarch were put to the test in 1848. During the course of the revolution the imperial family fled from Vienna, taking refuge in Olmütz (Olomouc). This provincial Moravian town was to become the scene of a spectacular handover of power. In the face of events, it was thought that the abdication of the enfeebled emperor Ferdinand could be used to give the dynasty an active role again. Franz Joseph’s father, Archduke Franz Karl, who was in fact the next in line to the succession, waived his right to the throne after forceful persuasion by his wife Sophie. Archduchess Sophie now saw that the moment had come to realise her lifelong dream of her firstborn son becoming emperor.

The choice of official name for the eighteen-year-old emperor is also revealing. At first it had been planned to let him ascend the throne with his first forename as Franz II, in memory of his grandfather, Franz I. The addition of his second forename was intended to recall the ‘People’s Emperor’ Joseph II, who was still revered by the common folk, resulting in the double name of Franz Joseph I, an unusual choice for the House of Habsburg.

However, the young emperor soon disappointed the hopes of progressive forces in the empire. Behind the youthful façade the old reactionary forces still held sway: the revolution was suppressed with great severity, its leaders persecuted, being forced into exile or, where they could be apprehended, executed or sentenced to lengthy terms of imprisonment.

An incident that reveals how unpopular the emperor was at the beginning of his reign was the assassination attempt on Franz Joseph in Vienna in 1853 carried out by the Hungarian journeyman tailor János Libényi, who wanted to avenge the severe treatment of the revolutionaries in Hungary. The emperor escaped with minor injuries, but the perpetrator was summarily hanged on the Simmeringer Haide, Vienna’s place of execution. A popular Viennese vernacular poem immortalized the event: ‘On Simmering Heath a tailor was hanged / Serves him right for making such a bad stab at it!’ The emperor’s lucky escape is commemorated by the Votivkirche in Vienna, erected on the initiative of his brother Ferdinand Maximilian.

The beginning of Franz Joseph’s reign was marked by rejection of demands for a constitution. The hopes raised by the draft constitutions devised by liberal forces from 1848 were dashed with the issuing of the ‘Silvesterpatent’ of 1851, which revoked the basic constitution. The policies of the young emperor were marked by the ideas of neo-absolutism. Franz Joseph saw himself as an absolute monarch, responsible only to God, ruling the body politic with sole authority, without obligation to the provisions of a constitution or the will of the people, in effect a continuation of the repressive policies of the Metternich era. The nucleus of the concept of the state was seen in the dynasty and in the Catholic Church’s support of the state. Franz Joseph regarded liberalism, which propagated the political, economic and religious freedom of citizens, together with general progress and emancipation from feudal authority, as a fundamental threat to his power.

His opposition to liberalism is also evident in his conservative view of the role of the Church. The traditional loyalty of the Habsburg dynasty to the Catholic Church was confirmed by the Concordat of 1855. This meant the end of the Josephinian State Church, with the Catholic clergy once again being given wide-reaching influence over marital and family law as well as teaching in schools, which was seen as a slap in the face for liberal forces.

Franz Joseph practised an authoritarian style of rule, believing that the power of decision should lie exclusively in the hands of the emperor. Young and inexperienced, he relied on those around him, in particular his mother and a number of extremely conservative advisors. Nonetheless, he was often overwhelmed by his enormous responsibility. The first years of his reign were marked by arbitrariness, lack of sensitivity and political short-sightedness resulting in a number of seriously ill-judged decisions.

The emperor’s greatest foreign-policy mistake was the position taken by Austria in the Crimean War (1853–1856), a quarrel between Russia and the collapsing Ottoman Empire centring on regions around the Black Sea that proliferated into a pan-European conflict. Franz Joseph declared Austria’s neutrality, thus snubbing the Russian tsar Nicholas I, his closest ally, who only a few years previously had provided vital assistance in suppressing the Hungarian revolution of 1848/49. This massive support from Russia should have welded together the two most reactionary regimes in Europe, the Russian and Austrian empires, but the alliance foundered on Franz Joseph’s indecision.

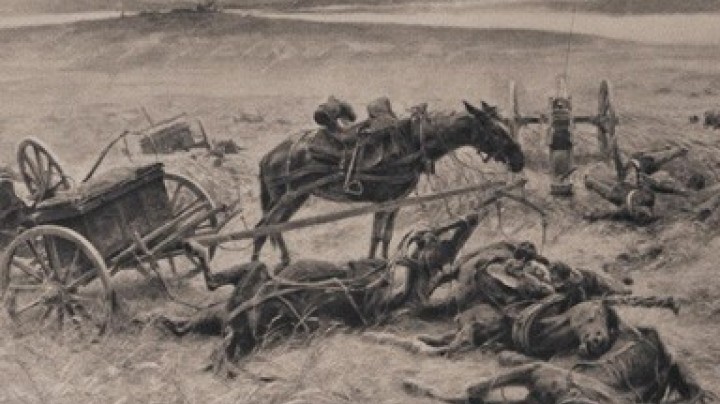

A further setback was the loss of the northern Italian territories during the Risorgimento, the struggle for Italian reunification. This was accompanied by a personal disaster: at the Battle of Solferino in 1859 Franz Joseph himself took supreme command, and when the battle ended in defeat for Austria his incompetence as a military leader was proven. Austria was subsequently forced to accept severe losses of territory. Lombardy, the richest province in the empire, was ceded in 1859, to be followed by Venetia in 1866.

Franz Joseph’s government was shaken to its very foundations by Austria’s humiliating defeat at the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866, which resulted in the final loss of Habsburg primacy among the German princes. Prussia assumed the leadership of the German states, thanks to Bismarck’s vigorous policies. When the German empire was founded in 1871, completing the unification of Germany, the ‘Lesser German’ solution prevailed, that is, the German states united under Prussian leadership to the exclusion of Austria. The Austrian Empire was thus forced into a policy of alliance with the economically stronger German Empire, which became the dominant Great Power in Central Europe, while the economically weaker and politically far less stable Habsburg Monarchy was forced into the role of a ‘junior partner’.