An encyclopaedia of the Monarchy

Emperor Franz Joseph could scarcely believe it; his son was writing his own articles for the monumental work Die österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild (‘The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in Words and Pictures’).

Literary review in: Mittheilungen des k. k. oesterreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunstgewerbe, Year 1 (1886), no. 1, page 10.We have Crown Prince Archduke Rudolf’s very own initiative to thank for the said work; its importance to Austria as a patriotic deed has already been mentioned in these pages. On a large scale, it is intended to render an overall picture of the Monarchy and its inhabitants in circa 15 volumes. The most outstanding writers and artists of Austria-Hungary have united in order to create under the leadership and with the collaboration of the Crown Prince an ethnographic and topographical description of the empire, of academic and artistic value and at the same time a book of the people which compares with no other, even outside Austria.

Following a concept which probably originated with Archduke Johann Salvator, the Kronprinzenwerk covered each crown land in a separate volume according to categories such as geography, history, national economy, folklore, art or transportation. Rudolf himself oversaw the introductions to the summary volumes as well as articles on places such as Vienna and Lower Austria.

However, the work was not entirely able to do justice to Crown Prince Rudolf’s academic ambition; while, as he stressed in the introduction, the individuality of the different peoples was recognized, due to the work’s political and administrative categorization according to crown land, it did not live up to the standards of contemporary ethnographic works, which preferred organization according to ethnicity. The essays describing the composition of the population (which reflect nineteenth-century anthropology’s belief in the ‘measurability’ of such data), and the folkloristic articles on the character of a people, its customs and folk literature, tended to be arranged in abrupt sequence without links, and were even contradictory in some instances. Added to this, there were stereotypical representations which conjured up ‘classic enemy stereotypes’, such as the description of the ‘thieving Gypsy’.

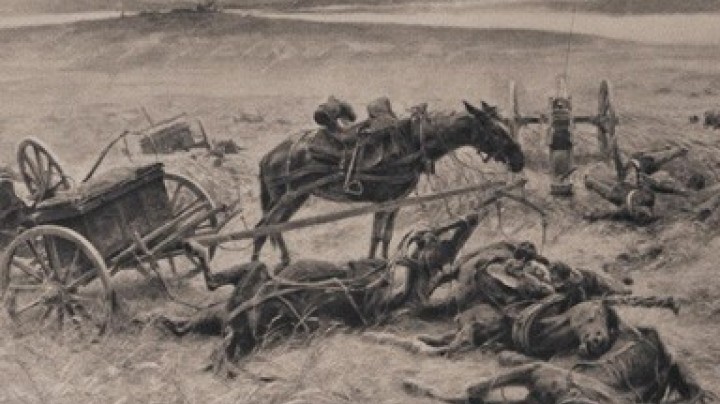

Many aspects of the publication reflect the ambivalences of contemporary society; while progress is celebrated, the displacement of traditional crafts, exploitation and the injurious effects of industrial labour on health are discussed, which is astonishing in view of the official nature of the work. This dichotomy becomes evident above all in the description of the peripheral regions of the Monarchy; a nostalgic view is taken of their intact traditions, characterized by their ‘backwardness’, yet modernization and the ascent to a ‘higher cultural level’ are deemed desirable.

On 1 December 1885, Rudolf handed his father the first issue of the German and Hungarian edition, which contained the introductory texts composed by him. Allegedly, at the reception held to celebrate the publication, Franz Joseph asked Maurus Jókai, who was in charge of the Hungarian edition, ‘Did my son really write this introductory article himself?’ Jókai himself recorded for posterity the fact that Franz Joseph’s ‘face radiated the heartfelt joy of a father’. However, the emperor’s subsequent lack of comprehension is said to have disappointed Rudolf.