Domestic music-making instead of festive operas – the end of the Baroque opera

In straitened times saving money was the order of the day – but that did not necessarily have to mean a lack of festivities, as proved by the new fashion for celebrating within the family circle.

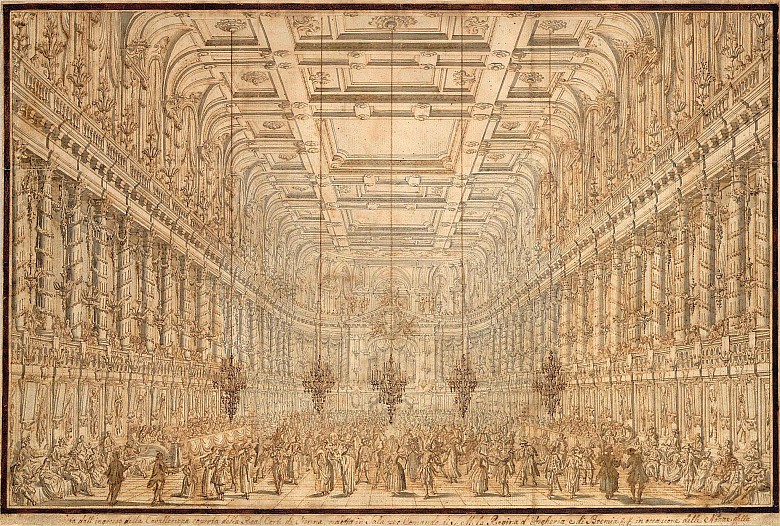

With the death of Charles VI in 1740 came the end of the elaborate Baroque festive opera. His daughter Maria Theresa had to cope with political and financial difficulties, with the wars marking the beginning of her reign proving an especial drain on her finances. She therefore had to limit theatrical activities at Court: in 1744 the last of the large-scale and extravagant opera performances took place to mark the marriage of Archduchess Maria Anna and Carl of Lorraine.

Subsequently performances were given on smaller stages such as the Burgtheater and the theatres at Schönbrunn and Laxenburg.

This turning away from large-scale performances was accompanied by a change in the way the Court presented itself to the outside world: in the era of Enlightened absolutism, music and festivities were no longer the central means of ceremonial display at European courts and interest in them waned. At the same time the ruling families retreated from the public into the private, familial sphere, in a sort of ‘bourgeoisification’ of their lifestyle. Court ceremonial changed, which also led to a move away from grandiose public performances of music to music-making in the family circle and theatrical performances in which courtiers participated.

Appointed co-regent by Maria Theresa after the death of his father in 1765, Joseph II was now in charge of opera and theatre. He was very thrifty by nature and keen to spend the smallest amount necessary on entertainment and amusements. In contrast to the Baroque era, the Court no longer provided the creative focus for the composers of the Viennese Classical period; their most important innovations left it largely untouched. The conditions for musicians and composers had changed: the Church and the Court relinquished their roles as patrons, while domestic music-making and public concerts became more important and a large number of music publishers and instrument-makers boosted the production of music. Joseph II held small chamber concerts three times a week, performed without an audience, at which he himself played the clavier, viola and violoncello.