Zita – to the very last for ‘God, Emperor and Fatherland’

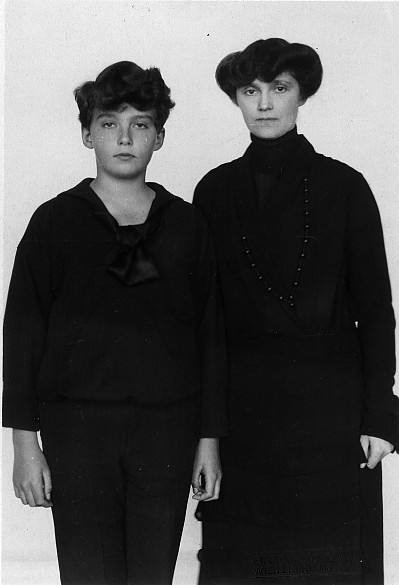

The long life of the last Austrian empress was marked by the political upheavals that changed the face of Europe during the twentieth century. However, Zita remained true to her principles: unconditional devotion to the Roman-Catholic Church and defence of the principle of legitimism, that is, the indeposability of the ruling dynasty of Habsburg-Lorraine.

Zita’s reaction to the suggestion that Emperor Karl should abdicate on 11 November 1918. Quotation from: Gordon Brook-Shepherd: Um Krone und Reich. Die Tragödie des letzten Habsburgerkaisers. Wien, München, Zürich 1968, S. 256Never! A ruler can be deposed... That is force, which precludes recognition. But abdicate — never! I would rather fall right here at your side. Then there would be Otto. And even if all of us here were killed, there would still be other Habsburgs!

Thanks to her iron will and intelligence, Zita became the definitive opinion leader in the family and the most important pillar of support for her husband, Emperor Karl I. She was generally credited with great political influence.

After the early death of her husband in 1922 Zita became the legal guardian of her eight children and upheld their claim to the succession in exile. She maintained regular and active contact with monarchist and clerical factions in the successor states of the Monarchy and lobbied for Habsburg interests in Western Europe. When her eldest son Otto attained majority in 1930, his position as head of the dynasty had been firmly established. The credit for this belongs above all to Zita, who had become the centre of the monarchist-legitimist faction in Central Europe.

From September 1934 Otto continued the work begun by his mother. However, she retained the role of influential advisor in the background, supporting her son as he became one of the leading figures of the monarchist Austrian resistance in exile to the National Socialist regime. In 1943 Zita was invited to talks with President Roosevelt in place of her son, who had fallen ill. This demonstrates the importance she was still accorded in political circles, even if her position as a monarch in exile lent her appearance in the United States a rather ‘exotic’ aura.

Always dressed in black, in keeping with strict Catholic tradition, the former emperor’s widow was assiduous in her commitment to achieve the beatification of her husband Karl. She spent her declining years in the St. Johannes-Stift, a church-run retirement home in the Swiss town of Zizers near the Austrian border. She was not allowed to enter Austria as she continued to refuse to sign the declaration waiving Habsburg claims to the throne.

It was not until 1980, when the Austrian Constitutional Court ruled that only those members of the family who actually had a claim to the throne according to Habsburg dynastic law were obliged to sign such a declaration in order to enter Austria – as one who had married into the family, Zita was not affected – that the last obstacle was removed. Federal Chancellor Bruno Kreisky advocated a ‘humane solution’, and thus it was that Zita was able to set foot on Austrian soil again in 1982. She visited the grave of her daughter Adelheid in the Tyrolean resort of Tulfes and met up with a number of her grandchildren in Innsbruck.

Her second visit, which took place a few months later, was undertaken in the public eye and had a more official character: Zita met the provincial governor of Styria, Josef Krainer, and went on a pilgrimage to Mariazell. Later she also visited Vienna, where a special mass in St Stephen’s Cathedral was held in her honour by Cardinal Franz König. More than 10,000 people turned up to get a glimpse of the former empress.

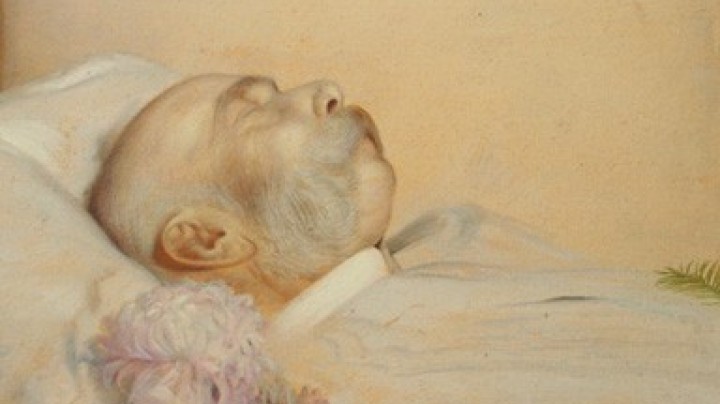

When she died at the age of 96 in 1989, her funeral, conducted in accordance with the traditional rites of the Viennese Court, was both a tourist spectacle and a symbol of reconciliation between the Republic of Austria and the House of Habsburg-Lorraine.