The Viennese waltz

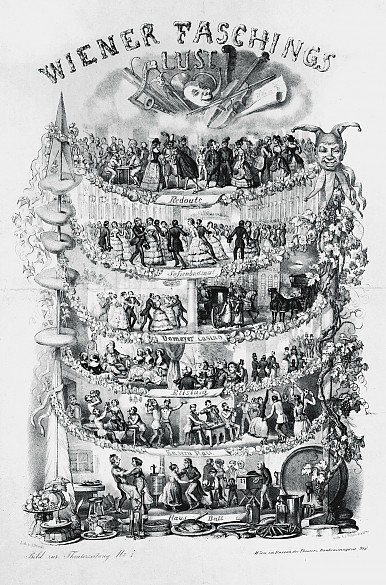

At the end of the eighteenth century a new dance ousted the minuet from the dance floor: the waltz. Vienna distracted itself with dancing, swaying in three-four time.

Graf de la Garde reportedAfter Their Majesties had left the orchestra began to play waltzes. Immediately an electric movement seemed to communicate itself to the entire numerous assembly. One has to see it with one’s own eyes in Vienna, how a gentleman in a waltz supports his lady in time with the music, lifting her in a flurry of steps, and how she surrenders to the sweet magic, a trace of giddiness giving her face an uncertain expression that increases her beauty. But one can also understand the power that the waltz exercises. As soon as the first notes are heard, faces clear, eyes quicken and a tremor of joy runs through them all.

To mark the death of Johann Strauss I, Eduard von Bauernfeld composed the poem ‘Das Leben ein Tanz’… Armes Wien! Die Götter haben

Dich nicht lieb mehr, einen sie nahmen

Dir Dein Liebstes – Deinen Strauß,

Deinen letzten Trost und Ruhm.

Was da singt und klingt und springt:

Alles harmlos: freud’ge Lust,

Heute fördern wir’s zur Ruhe,

heut’ wird das alte Wien begraben.

(…Unhappy Vienna! The gods no longer hold you dear, they have taken your most beloved One – your Strauss, your latest solace and fame. Whatever sings and sounds and leaps: all harmless: joyful pleasure, today we take it to its rest, today Old Vienna is going to its grave.)

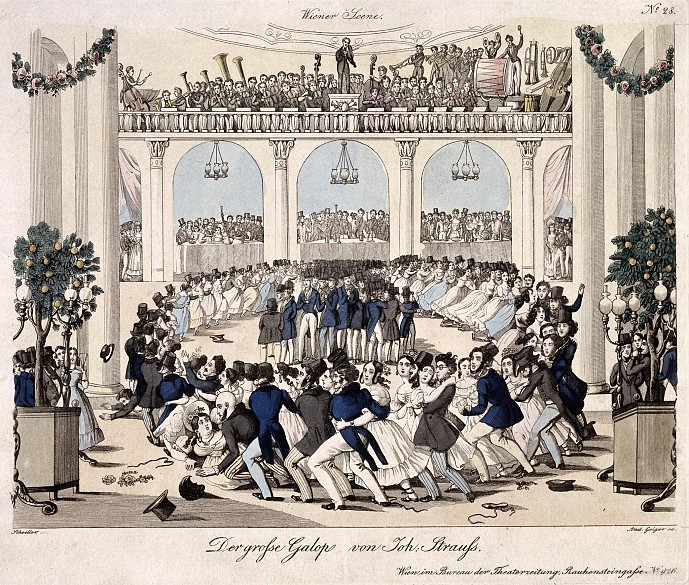

The most fashionable dance of the time, the waltz had developed out of the Ländler. The early waltzes were danced at a rapid pace and had complicated sequences of steps. The constant turning intoxicated the dancers and collisions were not uncommon. The authorities even considered banning the galop, a faster version of the polka. This passion for dancing was shared by all social classes; it provided a little freedom in an otherwise strictly regulated life, in particular during the carnival season.

During the Congress of Vienna numerous festivities and dances took place, opening the floor for the international triumph of the Viennese waltz. In the official part of these events polonaises and minuets were danced – but later on in the evening most of the younger guests revolved around the dance floor in three-four time.

The passion for dancing exhibited by the participants at the Congress became the target of mordant criticism: the Austrian field marshal Prince Charles de Ligne remarked wryly: ‘Le Congrès danse beaucoup, mais il ne marche pas’ (the Congress dances but does not move forward).

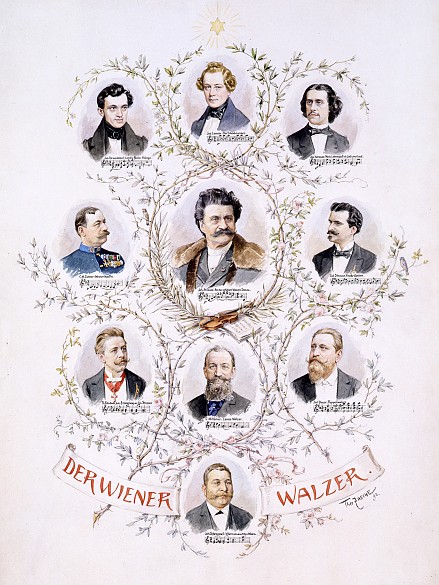

The waltz continued to blossom in the following years, but the directors of music found it increasingly difficult to satisfy the huge numbers of dancers at the new establishments. Originally comprising a small number of musicians, the dance orchestras had to be enlarged and new pieces composed and rehearsed. Joseph Lanner and Johann Strauss I put their stamp on the waltz, imbuing it with a special, specifically Viennese form. On the order of Archduke Ferdinand, the eldest son of Emperor Franz II (I), when played at a Court ball, a waltz should last exactly eight minutes. The older, saltatory style of dancing was abandoned; now couples glided smoothly in circles around the ballroom.

From 1830 the Viennese waltz was exported to other European cities: Johann Strauss I toured abroad, conducting performances in Germany, Belgium and England. The popularity of the waltz in its birthplace remained undimmed, a circumstance evidenced both by the sales of music publishers and the grand announcement of waltz premieres. In the Ringstrasse era the Viennese waltz was incorporated into the operetta.