The Seven Years’ (World) War

What began with the intention of taking revenge on Prussia for the loss of Silesia ended in a war that was waged both in and outside Europe. Austria found itself caught up in colonial conflicts between England and France, and the European system of alliances was changed fundamentally.

Maria Theresa sums up her motivation for going to warPrussia must be given a trouncing.

Maria Theresa’s proverbial love of peace was based on a wealth of experience – by the end of her life she was able to look back on many defeats. However, at the beginning of the Seven Years’ War, she was still thinking otherwise and wanted at all costs to win Silesia back from her arch-enemy Frederick of Prussia. To this end, she concluded an alliance with Russia and even one with France, which was a surprising move given that for centuries international diplomacy had been accustomed to seeing the Habsburgs and France at constant loggerheads. Later, Maria Theresa was to resort to a time-hallowed ploy to overcome these old animosities – after the Seven Years’ War, her daughters Maria Karolina and Marie Antoinette were married off to Bourbons.

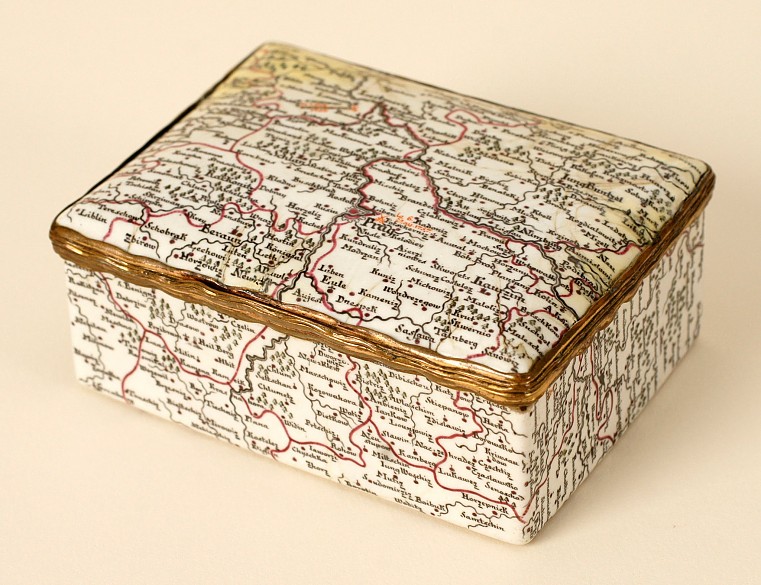

On 29 August 1756, the well-informed Frederick pre-empted Maria Theresa’s plans with a preventive offensive in the form of an invasion of Saxony. In the following year of the war, Austria received support from France, which for its part was already waging war against England over possessions in Canada, India, the Antilles and Minorca, on account of which the Seven Years’ War is also known, in the United States, as the French and Indian War. Sweden and Russia also joined this alliance, which, however, enjoyed no common supreme command and thus suffered from lack of coordination when confronted by Frederick’s modern strategic concept.

In 1757, the Habsburg forces under Daun scored one of their few victories at the battle of Kolin. Another morale-raiser was the occupation of Berlin in October 1757 by forces under Hadik’s command, though it was somewhat dampened by his having withdraw from the enemy capital the very next day. Far from Prussia being quickly defeated, problems arose in the form of financial shortages and tensions within the alliance, while France’s efforts were concentrated overseas.

Finally, peace talks at the castle of Hubertusburg in Saxony brought the long and bloody war to a close with a restitution of the status quo: Maria Theresa had to relinquish Silesia, in return for which Frederick promised that he would vote for her son Joseph when it came to the next imperial election. The Austrian army had suffered enormous losses: 300,000 soldiers, 82,000 horses and 260 million gulden plus enormous interest payments on loans. In spite of this far from glorious war, Austria remained a great power. But all its hard-pressed peoples were offered in return for their sufferings was a small measure of ‘prosperity and happiness’ (‘Wohlfahrt und Glückseligkeit’).