Ringstrasse palaces

The Ringstrasse project was not only a symbol of imperial power but also provided a stage for the Monarchy’s ascendant liberal upper middle classes.

The Ringstrasse became the sought-after address of the ‘second tier of society’: the people taking apartments here were the parvenus, disdained by the old aristocracy, the recently ennobled social climbers of the Monarchy, some of them Jewish, manufacturers, mercantilists and bankers. Their town places and apartment buildings now stood near the court and the homes of the nobility – a proximity that placed the upper middle classes on a par with the old aristocracy. The ‘first tier of society’, the high aristocracy, often considered themselves too refined for the Ring, and only two of the residential palaces on the Ringstrasse were owned by members of the imperial family. For them it represented the ostentatious display of instant riches that were often lost again as quickly as they had been gained.

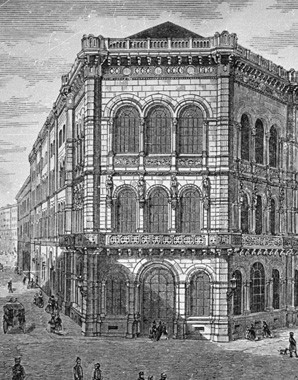

The new social and political elite’s need to display their wealth and status was also reflected in the façades of these buildings: the piano nobile or bel étage, the floor on which the owners of the building lived, was given particular emphasis. While aristocratic families together with their servants occupied the whole building, parts of the apartment buildings and palaces were let. The regulation limiting these buildings to four storeys was circumvented with a ruse – a mezzanine floor was inserted between the ground floor and the first floor. Separate staircases accentuated the social differentiation between owner and servants.

Many of the families who owned these town palaces hosted famous salons at which the arts world and the financial aristocracy met. The soirees for which invitations were most in demand were held by the Todesco family in their palace on Kärntner Strasse: at one of these gatherings Johann Strauss met his future wife, the opera singer Henriette Treffz, who at that point was having an affair with one of the Todescos. The financial settlement she received when this ended enabled Strauss to work undisturbed on his operetta Die Fledermaus, which became an international success.

Palais Leitenberger on Parkring was also one of the centres of Viennese society. The textile industrialist Friedrich Leitenberger was one of the major art patrons of his times. Among the regular guests here was Crown Prince Rudolf, who enjoyed the society of liberal and politically progressive thinkers. Rudolf sought Leitenberger’s financial support for the Wiener Tagblatt, the newspaper in which he published articles anonymously.