The peasant as ‘provider for the people’

The status of the peasant was upgraded. As ‘provider for the people’ of the Monarchy he was given a key role in food production by Joseph II. For this reason his poor living conditions were to be improved.

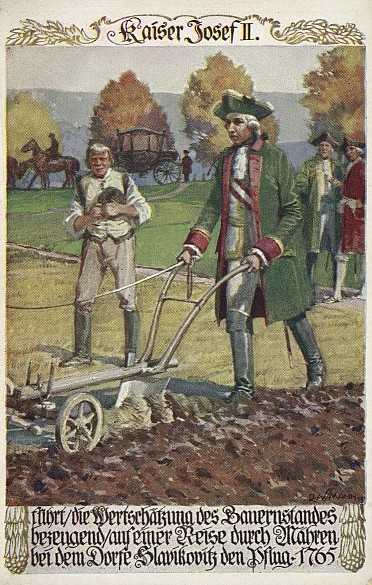

Under Joseph II the peasantry were given a central position. The physiocratic national economists were convinced that improvements in agriculture could ensure a solid basis for feeding the whole population. Joseph II was not above setting his own hand to a plough for the sake of publicity, to give expression to the value he placed on the peasants – and this, incidentally, brought him respect from the peasantry.

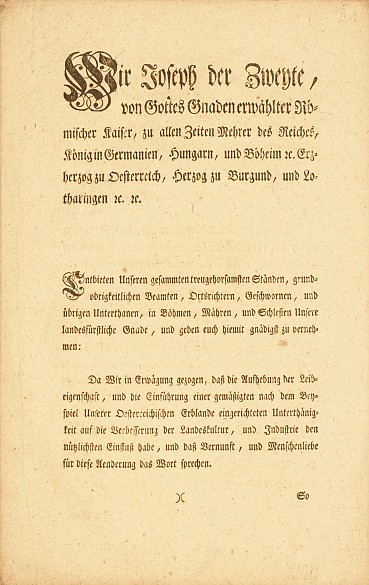

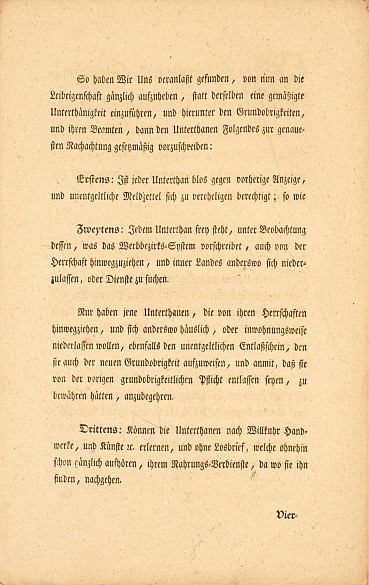

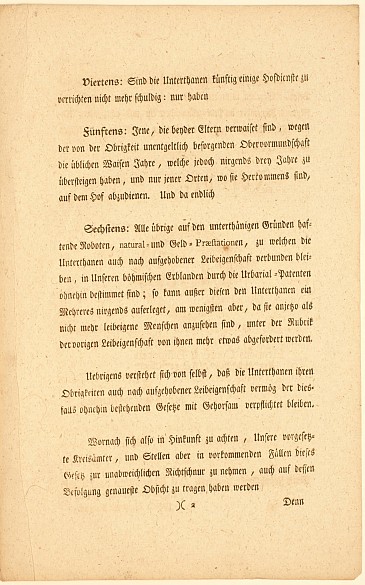

Joseph II had the causes of many grievances removed. These included, above all, the state of serfdom, which had a powerful effect on the legal and social status of many of his subjects. Serfdom was a harsher form of peasant dependency (though it should not to be confused with slavery). It made it possible for the landlord – normally a member of the upper classes, such as the nobility or clergy – on the basis of his lordship over land and soil to demand tithes and labour from his subjects: a certain part of the peasants’ harvest, which could vary from region to region, had to be surrendered, together with a certain number of days when the peasant had to work for his landlord without pay. In addition the rural population was in a relationship of personal dependency on the landlord. Serfs were not free subjects, and without the permission of the landlord they could neither marry nor leave their estates, nor exchange or inherit farms.

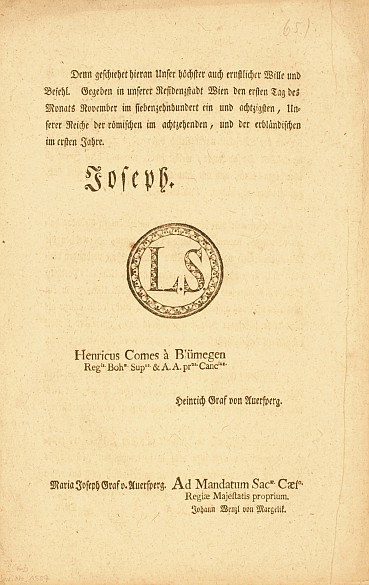

The idea of personal bondage, of course, contradicted the Enlightenment view of humanity, and also influenced the mobility of people, thus affecting the demand for workers which came with onset of industrialization. With the Patent for the Abolition of Serfdom in 1781 a landlord could no longer make arbitrary use of peasants. Peasants were entitled to leave a domain, to start families and to look for additional sources of income. With his new system of taxation, Joseph II sought to reduce the peasants’ financial burden. For the first time there was to be a fixed, unified rate of taxation, whereby the landlords were now only entitled to some seventeen per cent of the harvest, and had no possibility of obtaining any additional revenue. However, he was soon forced to withdraw this latter reform because of vigorous opposition from the landlords.

All that remained was the regulation on the abolition of serfdom. It was only in the aftermath of the revolution of 1848 that the remnants of feudal overlordship (tithes and obligatory labour) were finally abolished.