Luigi Lucheni: the man behind the file

We are extremely well informed about the murder of Empress Elisabeth, right through until she breathed her last on the ship on Lake Geneva. This makes her assassin’s fate all the more interesting – and the story of how he (or at least his head) was not laid to rest until the year 2000.

Empress Elisabeth was assassinated on 10 September 1898, stabbed with a file in the sixty-first year of her life.

What drove the young Luigi Lucheni to such a deed? Born in Paris in April 1873 as the son of a worker of Italian extraction, he grew up in an orphanage and was sent to work at the age of ten. At twenty he joined the army and took part in the Abyssinian campaign, subsequently being employed for a short time by the Prince of Aragon. By and large, however, Lucheni got by with casual work. His hatred of the aristocracy grew and grew – until he finally resolved to give vent to his embitterment with an assassination.

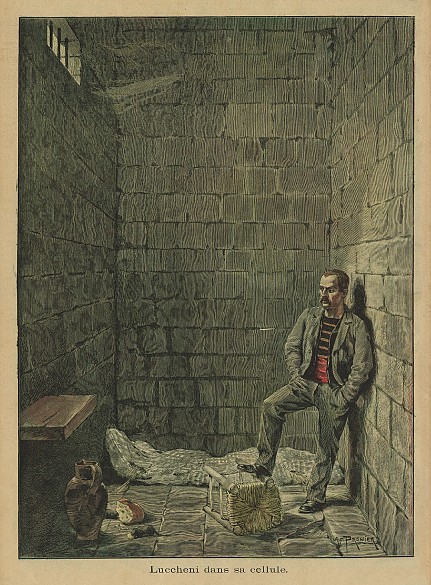

After having carried out his deed, Lucheni made no attempt to evade arrest and demanded the death sentence in order to go down in history as a political martyr. However, his application to be extradited to Italy, where this would have been possible, was refused and he was sentenced to life imprisonment under the laws of the canton of Geneva. Twelve years later he was found hung – or hanged? – with a belt in his dark cell. Although the official version was suicide, a number of elements in the story remain unclear – in any case, the prison staff will certainly have been glad to be rid of an inmate who was said to be difficult and underhanded.

Is it possible to perceive a certain predisposition in a murderer’s brain? Scientists examined parts of Lucheni’s body in search of the answer to this question, but without detecting any abnormalities. The cranium was then closed up once more and the murderer’s head preserved in a jar in formaldehyde. A description of 1920 runs as follows: ‘The fact that the fluid is not quite clear and has deformed the head a little gives it a somewhat gruesome look. The eyes are only half-open and the slightly contorted mouth open far enough to reveal teeth that are still in excellent condition.’ In 1985, Austria successfully applied for the head to be transferred to the Narrenturm, the home of the Federal Pathologic-anatomical Museum (Pathologisch-anatomisches Bundesmuseum) in Vienna. The object was on principle not intended to be put on public display, but certain occasions, particularly anniversaries, saw the Narrenturm so besieged by visitors that it was decided to halt the morbid curiosity by laying the head of Sisi’s murderer to rest at Vienna’s Central Cemetery (Zentralfriedhof).