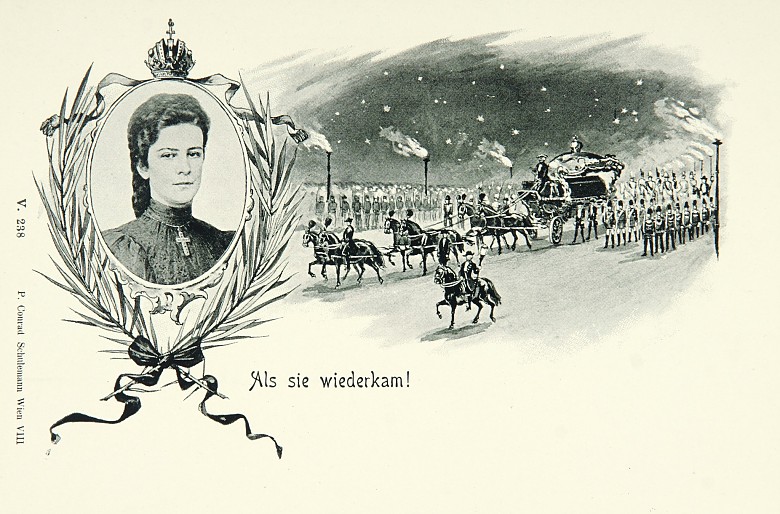

Death of a European traveller

‘The ship’s bell was already sounding as Elisabeth hurried along the quay with her lady-in-waiting.’ Just one possible opening for the last chapter of an historical novel on the life of Empress Elisabeth.

It is said that Rudolf’s suicide prompted Elisabeth to wear only mourning from that time on and to give away all her jewellery. She suffered from ever-deepening depressions, which in the last years of her life are thought to have developed into a kind of death-wish.

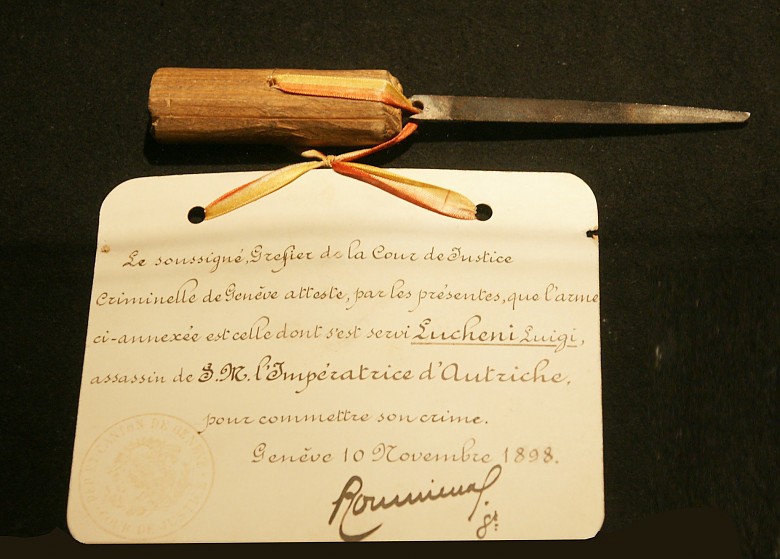

Elisabeth had travelled widely in the course of her life. On 9 September 1898, while staying incognito for a number of weeks at the Grand Hôtel de Caux near Montreux on Lake Geneva, she paid a visit to Baroness Julie Rothschild, wife of the Parisian Rothschild Adolphe and sister of the Viennese Rothschilds Nataniel and Albert. After her visit she stayed the night at the Hôtel Beau Rivage in Geneva in the company of her lady-in-waiting Countess Irma Sztáray. She used the pseudonym ‘Countess of Hohenembs’ but was recognized by the hotelier and the next morning the Journal de Genève informed its readers – who included the Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni – that the Empress of Austria was a guest in their city. Lucheni had in fact planned to assassinate Henri d’Orléans, pretender to the throne of France, who although expected to visit the city had ultimately failed to show up. For the anarchist, the prominent aristocrat Elisabeth was an equally suitable victim, likewise sure to attract media attention. When Elisabeth and her lady-in-waiting were walking to the Geneva-Montreux boat, Lucheni saw his chance and stabbed her in the heart with a sharpened file.

Initially, Elisabeth did not notice her lethal wound, thinking that the man had simply thrown her roughly to the ground. In his novel Arme schöne Kaiserin – Elisabeth von Österreich (‘Poor beautiful Empress – Elisabeth of Austria’), Erwin H. Rainalter has the lady-in-waiting ask ‘Does Your Majesty feel any pain? Are you wounded?’ ‘No, I don’t feel anything,’ replies the Empress, ‘I am just very frightened.’ Elisabeth walked about another hundred yards to the ship and finally collapsed after going on board. ‘The file went into the middle of the heart,’ reports the doctor who examines Elisabeth. ‘There is no hope – she is dead.’ His statement may have been true in a physical sense but given the personality cult that even now surrounds her person, one could almost describe her as ‘undead’. Her assassin was condemned to life imprisonment and committed suicide in 1910. His head was for a long time preserved in the Narrenturm, the home of the Federal Pathologic-anatomical Museum (Pathologisch-anatomisches Bundesmuseum) in Vienna, before finally being laid to rest in the Anatomical Graves at the Central Cemetery (Zentralfriedhof).