The emperor’s new clothes – Joseph II’s break with tradition

After the heyday of Rococo pomp at the court of Maria Theresa, Joseph II made a spectacular mark in the very first year of his co-regency, wholly in keeping with the utilitarian tenor of the Enlightenment, by abolishing the Spanish Mantelkleid, the embodiment of ceremonial tradition at the Habsburg imperial Court.

The Mantelkleid evolved from Spanish court dress of the sixteenth century and essentially consisted of a richly-embroidered cloak worn with a feathered hat and breeches. Retained unchanged in its archaic form at the Habsburg imperial Court, it was the sole permitted dress for public positions at Court. When Joseph ordered the abolition of this symbol of the quasi-religious exaltation of His Imperial Majesty in 1766, the alarm bells started to ring with the conservative guardians of Habsburg tradition. The latter feared that allowing military uniform to be worn at Court – here Joseph’s admiration for the Prussian king Frederick II is evident – represented a dangerous break with the exclusive symbolic language of the Viennese imperial Court.

After the death of Maria Theresa in 1780, Joseph had a free hand as ruler: further radical interventions in the way the Court was run took place. Joseph now marked the new era that had dawned by calling a halt to showcase imperial projects in favour of buildings for public use. At Schönbrunn, the pet project of his late mother, who had commissioned extensive remodelling and alterations in the palace and gardens right up to the last, only the most necessary maintenance work was given imperial approval.

At the Vienna Hofburg, which continued to be used as a residence, Joseph occupied one suite of rooms in the Leopoldinischer Trakt, today the offices of the Federal President. On the mezzanine floor below is the ‘Kontrollorgang’ (lit.: controller’s passage), where the emperor held his legendary audiences, which were open to everyone, demonstrating his wish to be the people’s emperor.

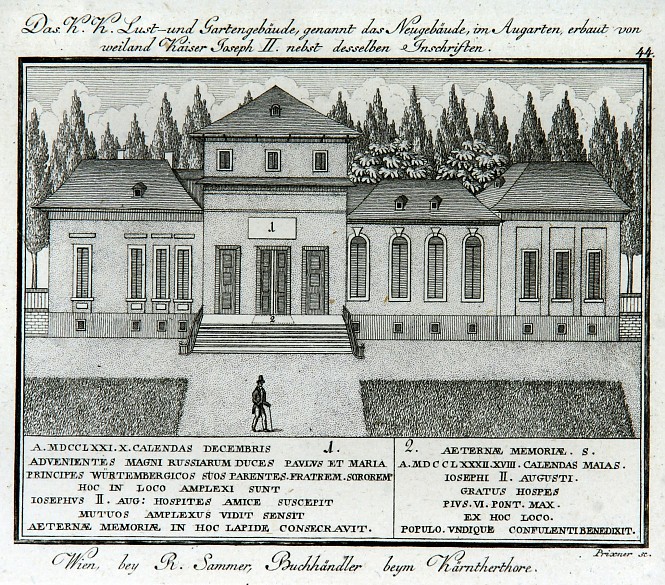

The emperor’s personal aversion to courtly pomp in the private sphere can be seen clearly in the Josephsstöckl in the Augarten. Less a palace than a villa with garden, it was built in 1780–83 and shows Joseph’s modest demands for comfort: a plain, asymmetric edifice with well-lit rooms arranged on the principles of practicality and affording views of the park that surrounds it.