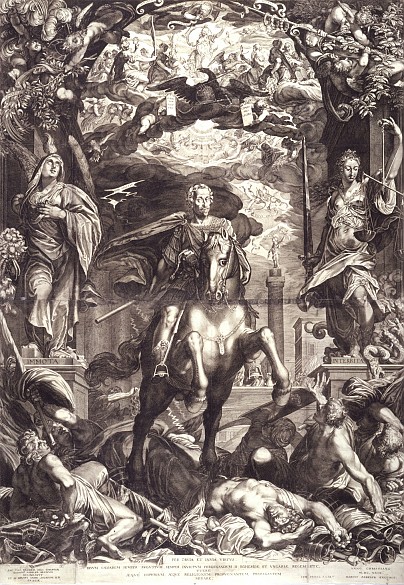

Emperor Ferdinand II intoxicated by power

After the suppression of the Bohemian rebellion Ferdinand II was at the height of his power. However, the war was not over: on the contrary, it spread.

From the chronicle of the Thirty Years’ War by the Aulic Councillor Count Volkmar Happes, concerning the year 1629The greatest misfortune, and one to be lamented with tears of blood among a number that have taken place in this year, is that in many places the Papists have driven out the pure teaching of the Gospel and have brought back the anti-Christian monstrosity of popery, at the religious foundations of Halberstadt and Walkerode, for example, and in Minden, Bremen, Illfeld, and other places. This year also saw the publication of the troublesome religious edict of Emperor Ferdinand II.

Not only in Bohemia but in all the Habsburg lands, 1620 was the year in which all the non-Catholic groupings both figuratively and literally ‘got it in the neck’. The ‘Vernewerte Landesordnung’ (renewed ordering of the land) of 1627 was the last of a series of measures designed to establish Absolutist rule in Bohemia, which it declared to be a Habsburg hereditary land. Within a short time the other Habsburg lands were also re-catholicized and all other Christian confessions prohibited.

Although Emperor Ferdinand suppressed the Protestant Reformation with great brutality, it required a lengthy period of time and intensive activity on the part of the new religious orders to bring his lands back to Catholicism. This more peaceful programme involved the schools of the Jesuits and Piarists, universities, the construction or rebuilding of churches and monasteries in the Baroque style, pilgrimages, and the veneration of St John Nepomuk, which was particularly highly developed in the saint’s native land of Bohemia. Although now only Catholicism was permitted, many people in the hereditary lands continued to practise their Protestant faith in secret.

The Thirty Years’ War initially went well for Ferdinand II. After his victory in Bohemia, the Catholic troops advanced into the Palatinate, Westphalia, and Lower Saxony. They were now faced with another opponent standing up to defend Protestantism, the Danish king Christian IV, who received financial support from France, England, and the Netherlands. However, the Catholic armies – with Tilly in command of the League’s armies, and Wallenstein of the imperial forces – succeeded in scoring victories over Denmark.

At the end of the 1620s Ferdinand was at the height of his power and the Danish king was forced to capitulate. In 1629 Ferdinand II issued the Edict of Restitution ordering the restoration to the Catholic Church of all ecclesiastical estates lost since the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, which constituted a major threat to numerous Protestant areas. With this measure, however, Ferdinand was pushing his luck too far, as it clearly put paid to the tradition of the emperor as the guardian of law and peace in the Holy Roman Empire. Now even his allies took fright and put up resistance. In 1630 the princes of the Empire dismissed the most important imperial commander, Wallenstein, who was replaced by Tilly. From this point onwards Ferdinand II found that his uncompromising policy was bound to lead to setbacks.