Elisabeth as an outsider

Elisabeth indulged in extreme individualism, increasingly making her an outsider in the world of the Viennese court, which was ruled by convention.

Poem by Empress Elisabeth; source: Hamann, Brigitte: Elisabeth. Kaiserin wider Willen, München 1981, p. 607Titania shall not go among people

In this world, where no one understands her,

Where a hundred thousand gawpers beset her,

Whispering inquisitively, “Look, there’s that foolish woman, look!”

Where Resentment spies enviously upon her,

To twist her every action.

May she return home to those regions

Where allied, kinder souls abide.

Elisabeth made no secret of her dislike of the fossilized traditions of the Viennese court. Her liberal attitudes led to her developing doubts about the viability of the Monarchy. She saw herself as a foreign body in court society and withdrew increasingly from her duties as empress. Her last major appearance in public at the side of Franz Joseph took place in 1879 on the occasion of their silver wedding anniversary, when the City of Vienna held a large-scale pageant that was also intended to celebrate the opening of the newly constructed Ringstrasse.

Notwithstanding her rejection of the constraints associated with her position as empress, she made use of the privileges that came with her rank, in particular the means to finance her extravagant and costly lifestyle. Her passions swallowed huge sums of money.

One of the outlets Elisabeth used to gain her freedom was her passion for travelling. Her restless nature could only be satisfied by constantly seeking out new destinations. Elisabeth loved the open sea and ocean voyages. Here her propensity for the unconventional also manifested itself: she had herself tattooed like a sailor, returning from one voyage with an anchor on her right shoulder, to the horror of Franz Joseph.

Elisabeth was also capable of acting with an astonishing lack of regard for convention within the family. She fostered her husband’s relationship with the actress Katharina Schratt. The empress saw this as a way of escaping her marital obligations yet at the same time ensuring that her husband was ‘in good hands’, as the actress was able to provide the ageing emperor with the atmosphere of intimate affection and human warmth that Elisabeth was constitutionally unable to give him.

Tragedy struck in Elisabeth’s life when her son Rudolf committed suicide in 1889. Increasingly afflicted by her fear of ageing, she took refuge in melancholy and withdrew from public life, dressing exclusively in black. Elisabeth suffered from depression and began to cultivate a morbid longing for death.

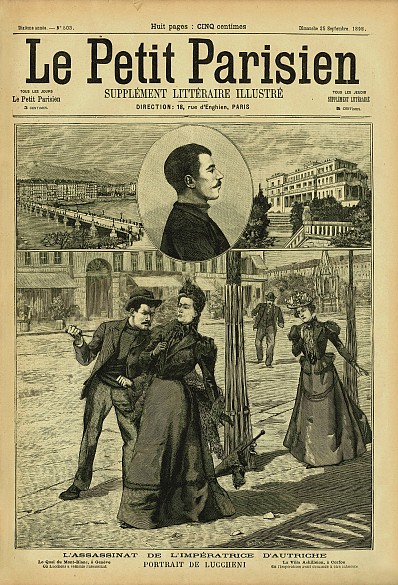

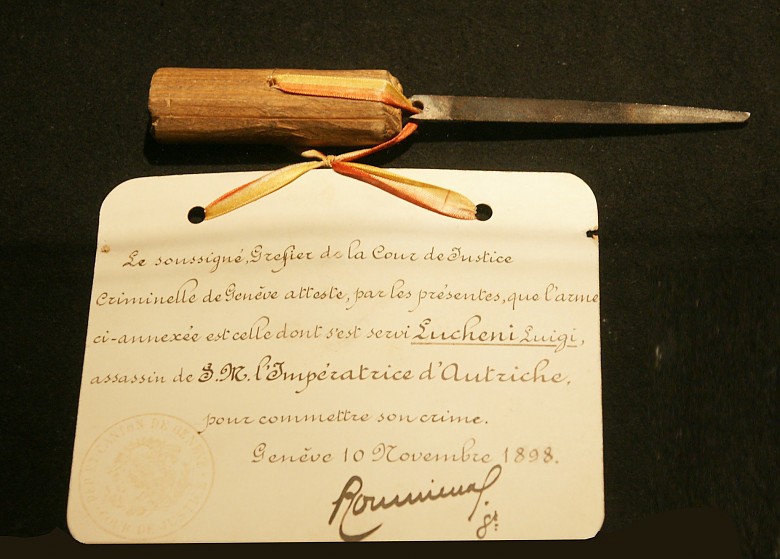

Her death by assassination on the lake promenade at Geneva on 10 September 1898 released her from an existence that had increasingly become a burden to her.

Elisabeth was laid to rest in the Imperial Crypt of the Church of the Capuchin Friars in Vienna.