Crisis in the highest circles – Economic boom and stock exchange crash

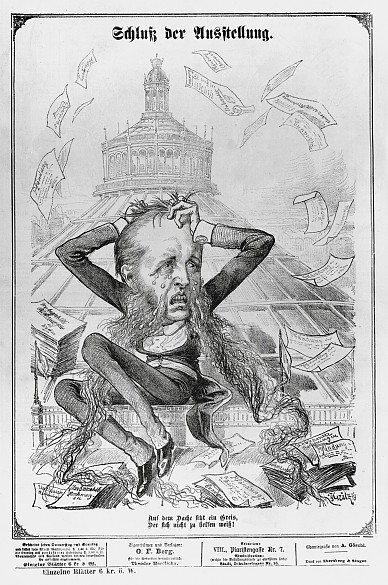

‘Ringstrasse Barons Bankrupt’ – ‘Crisis Reaches the Court’ – ‘General Plunges to his Death’ – ‘The End of the Boom?’ – that is how the newspaper headlines might have reported the stock exchange crash of 1873.

The stock exchange crash of May 1873 put an abrupt end to economic growth in the Monarchy, as well as to the wealth – and in some cases the life – of many of the so-called Ringstrasse barons from the second tier of society. Those whose finances did not survive the crash included not only bankers but also some members of the imperial court and confidants of the Emperor. The whole affair even affected the imperial family itself, since Archduke Ludwig Viktor, Franz Joseph’s brother, also lost money through speculation.

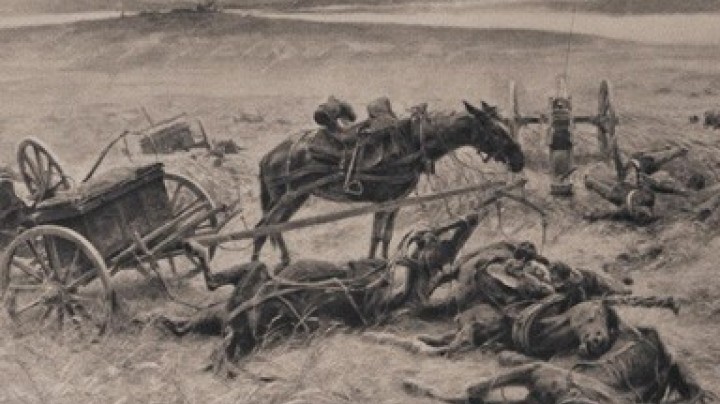

Baron Gablenz, the highly paid army commander of the army, likewise lost both his money and his possessions as a result of speculation. He turned to the Emperor, sending him a telegram in which he asked for financial support. The request, however, did not reach him, because the Emperor’s adjutant-general, Count Bellegarde, wanted to protect the Court from involvement in a scandal. The commander thought that he had incurred the Emperor’s displeasure and committed suicide.

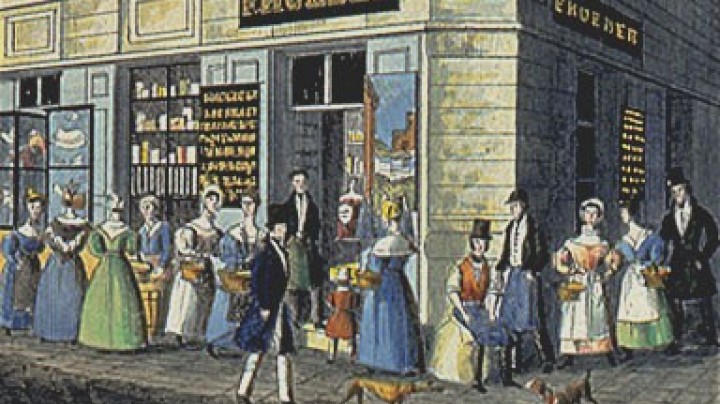

Until the stock exchange crash the economy had boomed in Vienna and throughout the Monarchy. A large number of businesses in both trade and big industry, banks and joint-stock companies had been founded. Just in the first period of the Gründerzeit following the compromise with Hungary and the ‘miracle harvest’ of 1867 more than 1,000 joint-stock companies were established and the Monarchy’s railway network almost doubled in size – a clear indicator of economic growth. In Vienna the construction of the Ringstrasse boulevard gave the building sector a boost, and the prospect of the World Exhibition provided further stimulus. The boom led to an increase in the cost of living. It was industrial workers and owners of small businesses that were particularly affected by high rents and food prices – they saw their real incomes fall.

Much of the economic boom during the Gründerzeit was based on pure speculation and on the foundation of banks and companies that existed only on paper. On 9 May 1873. which became known as ‘Black Friday’, prices on the Vienna Stock Exchange plummeted, leading to panic sales of shares. Even the National Bank could not intervene and provide support because it did not have enough reserves available.