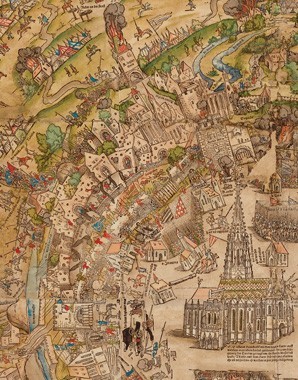

Charles V and the empire ‘on which the sun never set’

With possessions in Europe and America, Emperor Charles V ruled over vast territories and was enormously wealthy. It was during his reign that the Habsburgs were divided into a Spanish and an Austrian line.

Charles in his deed of abdicationI had great hopes – after so many great labours, only a few of these hopes have been fulfilled and only a few remain to me now. This has finally made me tired and sick.

Charles V was one of the most important European rulers of the early modern period. He entertained high ambitions, inherited massive territories, and had access to huge financial resources through the discoveries made on the American continents. He undertook many laborious journeys into the lands he ruled in Europe. Although he spoke several languages, he had little knowledge of German. At the age of seventeen he travelled to Spain to take up his royal inheritance at the court of Madrid. Only when he arrived there in 1516 did he make the acquaintance of his younger brother Ferdinand, who had in fact been the Spaniards’ first choice as king.

Following the death of his grandfather Maximilian I, Charles was elected King of the Romans; financial support from the Fugger banking family enabled him to outdo the bribes offered by his main competitor the French king Francis I. In 1520 he took the title ‘Emperor Elect’; his coronation in 1530 was to be the last at which a Holy Roman Emperor was crowned by the Pope. When Charles’s brother Ferdinand received the Austrian territories and the governorship of the Holy Roman Empire, the foundations were laid for the division of the house of Habsburg into an Austrian and a Spanish line.

Like most of the members of his family, Charles was very religious. Although he dreamed of a united Christendom, the spread of the Reformation was to set history on another course. With the Edict of Worms of 1521, Charles V put the leading reformer Martin Luther under the ban of the Empire. The opening of the Council of Trent marked the beginning of the Counter-Reformation. Although Charles enjoyed short-term success in the Schmalkaldic War of 1546/47, in 1555 he was compelled at the Peace of Augsburg to make far-reaching concessions to the Protestants.

Charles V’s policies were not only determined by internal religious conflicts: he also had to deal with enemies beyond his borders. Large periods of his reign were marked by wars against France and the Ottoman Empire, which Charles was able to finance with gold and silver from lands conquered in America.

Charles finally laid down his office in 1556, abdicating from the Spanish throne in favour of his son Philip and being succeeded as Holy Roman Emperor by his brother Ferdinand.