Censored!

Whether words, pictures, or music, nothing was unaffected by censorship. Even musicians had to defer to the strict regime – political statements could have far-reaching consequences.

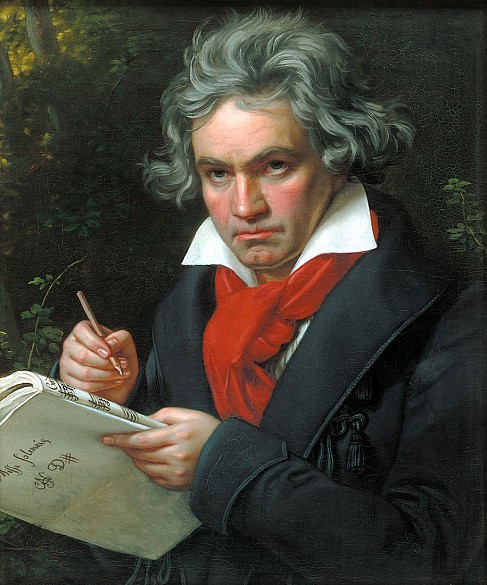

‘But musicians are immune to the censors – nobody knows what they are thinking when they compose.’ This comment on the complicated relationship between politics and the arts in the Biedermeier period was made by Franz Grillparzer in one of Beethoven’s conversation books. However, composers did suffer under the strict censorship just like other creative artists – political or philosophical subjects were considered as suspicious and constantly monitored by the authorities. And yet music was far from limiting itself to the ‘true chattering’ that Chancellor Metternich demanded of it. On the contrary, it was used as a vehicle for political messages, as in works such as the Marseillaise or Joseph Haydn’s imperial anthem. During the Congress of Vienna, Ludwig van Beethoven composed several works in honour of famous personages, though later his works display no connections with contemporary events. Franz Schubert also wrote practically no works in honour of the Emperor after 1815.

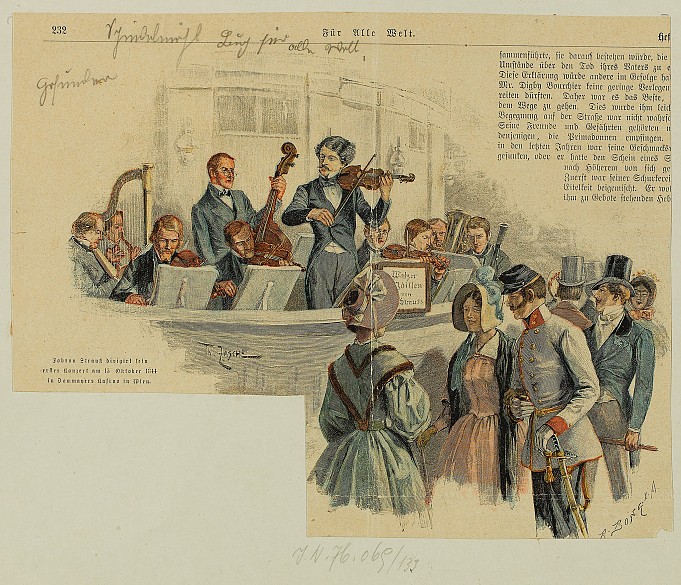

Even though critical content inevitably met with the disapproval of the authorities, music could not afford to retreat from the public sphere entirely, as musicians and composers alike were dependent on the support and goodwill of patrons. 1848 saw a split in the musical world, when Johann Strauss I composed works like the Radetzky March, dedicated to the imperial general Field Marshal Johann Josef Wenzel Radetzky, while his son Johann Strauss II put himself firmly on the side of the revolutionaries with compositions such as the waltz Songs of Freedom or the Revolution March. In the 1850s, the stance he had taken in 1848 caused him to be temporarily denied appointment as court director of ball music (‘k. k. Hofballmusik-Direktor’); a source originating at the highest level of the police records that he was regarded as a ‘frivolous, immoral, and wasteful person,’ who had ‘only recently begun to live a more orderly life.’