Be fruitful and multiply

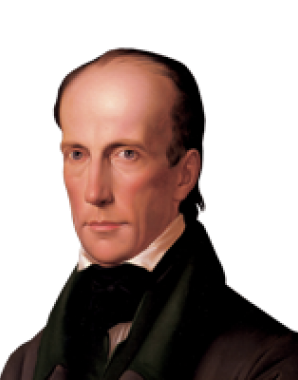

The Habsburgs’ offspring problem was solved by the highly productive Archduke Leopold and his wife Maria Ludovica.

Joseph II to his brother LeopoldDear brother, you cannot make me more obliged to you than by continuing to bring healthy children into the world that are like you. They will always and on every occasion be mine, the state is well served by them, and I am relieved of the obligation to enter into matrimony, a thing I abhor.

The marriage of Leopold and Maria Ludovica of Bourbon-Spain took place in Innsbruck on 5 August 1765. The consummation had to wait until well after the first night, as Leopold was ill with diarrhoea. As the head of the Court household Khevenhüller-Metsch wrote in his diary: ‘But as Archduke Leopold was still in a state of weakness, one did not feel so bold as to allow him to go in to his bride, and on account of his poor health he still had to sleep apart from her for a good time after.’ Despite this inauspicious start, the marriage was to bring forth many children.

It was while staying in Innsbruck for the wedding that Leopold’s father Franz Stephan died. As Leopold was his heir as ruler of Tuscany, the freshly married couple immediately moved to Florence. They achieved success both in their public and in their private lives: ‘Pietro Leopoldo’ became a highly respected figure and his wife bore him children at a rate approaching one per year, on account of which Joseph II gave his brother the ironic epithet ‘the splendid populator’. His numerous progeny averted the danger of Habsburg extinction, and Joseph was spared the ordeal of a third marriage.

Maria Ludovica bore Leopold a total of sixteen children, exactly as many as Leopold’s own parents had produced, leading to the formation of several lines of the house of Habsburg-Lorraine: the imperial line, carried on by Emperor Franz II (I); the Tuscan line, founded by Leopold’s successor Ferdinand III; the Hungarian line, founded by Archduke Josef Anton, Palatine of Hungary; and the lines of the archdukes Karl and Rainer. Although he did not found a dynastic line of his own, Archduke Johann lived a life that was full of incident and excitement.

Like many of his male relatives, Leopold had a highly active love-life outside the marital bed. At the time, it was considered perfectly acceptable for noblemen to keep mistresses. For the young dancer Livia Raimondi, for example, Leopold established a small palace in Florence, and in 1788 she bore him an illegitimate son who was named Luigi. Leopold even took two of his Tuscan mistresses with him to the court of Vienna. Empress Maria Ludovica appears to have come to terms with his affairs and is said to have cultivated friendly relations with her husband’s lovers.