O Christmas Tree – the Habsburgs and the Christmas tree

A festively decked tree with candles is today the foremost symbol of Christmas. However, this has not always been the case. It was not least the Habsburgs themselves who were responsible for introducing this custom in the lands of the Habsburg Monarchy.

Christmas trees as we know them today first arrived in Vienna during the Biedermeier, evidently from northern Germany. In Protestant countries Christmas had long been celebrated as a festivity of the middle-class family, as an intimate, emotional experience of the birth of Jesus – in contrast to the publicly celebrated, convivial church festivity of the Catholic tradition. The ‘new’ tranquil Christmas celebration round the Christmas tree came to epitomize a pious sense of family and bourgeois domesticity in the Habsburg monarchy during the Biedermeier era.

This rapid change of emphasis and its ready acceptance in Vienna can be explained by the profound social changes taking place in the capital during the reign of Joseph II and the Biedermeier era: the new economically flourishing patrician class began to assume a leading role during the time of the industrial revolution and was seeking new modes of expression for its sense of family values.

In 1814 reports compiled by Metternich’s state police contain the first mention of a Christmas tree festivity held in the salon of the Arnsteins, a Jewish banking family. Those attending were given lavish gifts, a custom that was not usual on Christmas Eve in Vienna at the time. The mistress of the house, Fanny von Arnstein, was from Berlin and had brought the custom with her from her native city.

However, it was via court circles in Vienna that the Christmas tree spread rapidly to the living rooms of the middle classes. The wife of Archduke Karl, Henriette of Nassau-Weilburg, who came from a Protestant family, brought the custom from her German home. Christmas 1816 saw the first Christmas tree, festively decked with candles, in the Habsburg family. Emperor Franz I attended this celebration and was so taken with the magical aura of the Christmas tree that he ordered a tree to be put up in the Hofburg at Christmas from then on. Subsequently it became the norm in Catholic families to celebrate Christmas round the tree: contemporary accounts record that while it was still almost impossible to procure a Christmas tree in 1821, by 1829 there were already street vendors selling trees at the Schottentor, the city’s north gate, and in 1851 the Am Hof square is said to have resembled a forest in the run-up to Christmas.

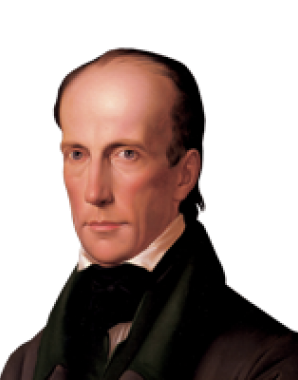

However, these changes in the way Christmas was celebrated were often regarded in a critical light. Archduke Johann, who witnessed the first Christmas tree festivities in the Habsburg family, deplored this new fashion with its loss of religious meaning and increasing focus on lavish present-giving: ‘In the evening I visited ... Brother Carl. As it is Christmas Eve, all the children and those of us who are here had gathered together. Although I derived some pleasure at seeing all the little ones who constitute the hope of the dynasty, I was immediately put in a bad humour by the excessive heat from the many candles. In the old days, when I was a young boy, there was a nativity crib, which was illuminated, together with sweetmeats – and nothing more. Now there is no longer a crib! We saw a Christmas tree laden with sweetmeats and little candles, and a room full of all kinds of playthings, some of which were truly beautiful, and many things that in only a few weeks will be smashed, trampled or lost, and which surely cost a thousand gulden. ... Finally, as ... I wandered through room after room, finding no corner of the house I recognised, all that pomp, made with such extravagance, it became alien to me; I felt utterly lonely and was incapable of putting on a cheerful face.’