The Karlskirche

The Karlskirche in Vienna was built to impress. However, the church is notable not simply for its monumentality: what escapes most onlookers today is the complex symbolic programme that can be read from the individual elements of its architecture.

Old Testament, 1 Kings 7:21And he set up pillars in the porch of the temple: and he set up the right pillar, and called the name thereof Jachin [Hebrew: He (God) raises up]: and he set up the left pillar, and called the name thereof Boas [Hebrew: in Him is strength].

When plague broke out in Vienna in 1713, Charles VI pledged to erect a church in gratitude for the deliverance of the city. It was to be dedicated to St Charles Borromeo, venerated for his tireless efforts to bring succour to plague victims in Milan in the sixteenth century, and regarded as an exemplary saint of the Counter-Reformation. The intended message of the edifice was that like his patron saint, the emperor’s concern was for the welfare of his subjects.

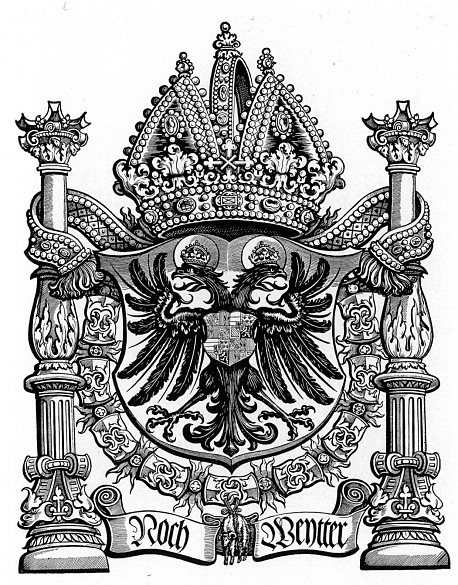

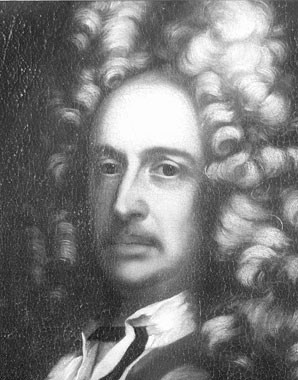

While the Court architect Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach was responsible for the architectural design, the underlying ideological conception was elaborated by a circle of scholars headed by the philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and the imperial Court antiquary Carl Gustav Heraeus, a specialist in ancient history and symbolism. The linking of symbols from Christianity and antiquity makes this major work of central European Baroque into a monument to the dynasty’s claim to universal emperorship under the banner of Christianity.

The severe monumentality of the architecture features a wealth of citations from classical antiquity in a language of forms worthy of an imperial building project: crowned by a cupola, the edifice is accessed via an entrance in the form of a temple portico flanked by two triumphal columns. However, as a sign of Habsburg humility the emperor yields these symbols of sovereignty to the saint: the reliefs on the columns relate the virtuous deeds of Charles Borromeo.

Nonetheless, the motif of the columns in itself is laden with symbolism referring to the emperor who had commissioned the church: in the language of art, columns are symbols of steadfastness and here stand for the personal motto of Charles VI, Constantia et fortitudo (Latin: ‘steadfastness and strength’). They also recall the two columns in front of the temple of Solomon. Charles thus positions himself as the successor of Solomon as a king of peace. They can also be interpreted as the Pillars of Hercules, a favourite symbol of Charles VI, by which he sought to compensate for the dynasty’s painful loss of Spain. In antiquity this motif symbolised the end of the known world, the Straits of Gibraltar. Charles’s ancestor and model, Charles V, on whose empire ‘the sun never set’, chose it as his symbol, accompanied by the motto Plus ultra (Latin: ‘further still’), in order to assert the Habsburgs’ claim to global dominion.