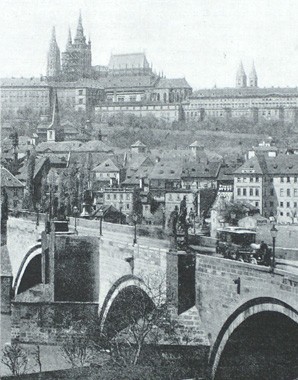

The Royal Castle at Prague

Prague Castle is a royal residence that could have come from the pages of a book of fairy tales. Looming majestically over the city, the ancient castle is the symbol of the Bohemian body politic. From the Middle Ages onwards, Prague Castle was the centre of the country’s secular and religious power. The start of Habsburg rule marked the beginning of a history of rapprochement and rejection.

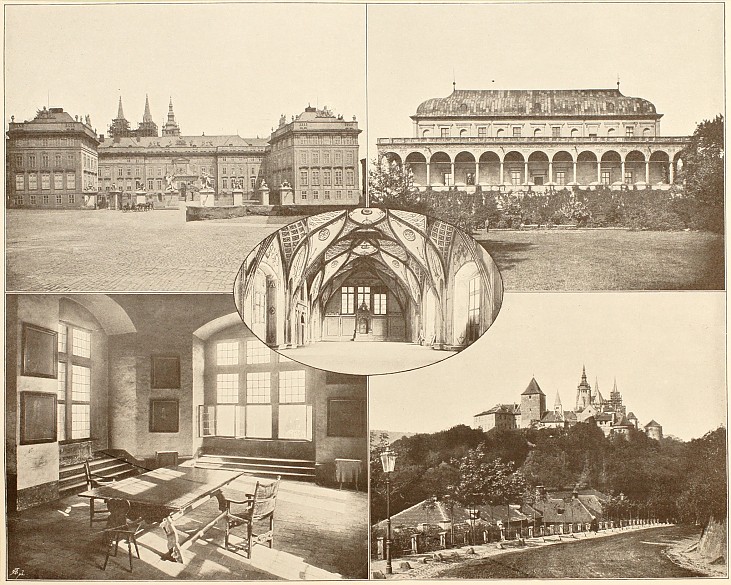

The Royal Castle contained the royal residence and was where the Diet and the supreme authorities of the Kingdom of Bohemia met. Hard by the palace is St Vitus’ Cathedral, symbol of ecclesiastical power. The cathedral contains Bohemia’s holiest shrine, the chapel of St Wenceslas with the relics of its patron saint. The royal crown of Bohemia, known as the crown of St Wenceslas, is preserved in the cathedral’s treasury.

In the Royal Vault lie the remains of a number of Habsburgs, including Ferdinand I, who acquired the Bohemian crown for the Habsburg dynasty in 1526. His wife Anna, whose Jagiellon descent gave him a claim to the crown, is commemorated in the Belvedere in the castle’s Royal Garden, a graceful edifice in the Italian Renaissance style which when first built must have presented an exotic contrast to its Gothic surroundings.

Under Maximilian II the imperial Habsburg Court commuted between Vienna and Prague, until Rudolf II made Prague his permanent residence in 1583 and set about extensively remodelling the castle. His huge collections of art made the whole of Prague Castle into one large ‘cabinet of art and curiosities’. Today Rudolf’s fabled presence in the castle is recalled by a gold R on the tower of the cathedral and above all by the myth of ‘magic Prague’.

After the violent suppression of the uprising of the Bohemian estates in 1620, the Habsburgs avoided Prague, preferring to reside in Vienna. From then on, the Habsburgs rarely visited the ancient royal castle at Prague. Not only the imperial residence but also the central Bohemian authorities were now permanently transferred to Vienna.

Imperial pomp was now only seen during the rare sojourns of the Habsburg Court in Prague. One of these occasions was the festivities held to mark the coronation of Charles VI: hoping in vain for a male heir, Charles underwent the elaborate coronation ceremonies relatively late, in 1723, twelve years after ascending the throne. Allegedly he did so solely on account of an ancient legend which predicted that a male heir would only be born to a rightfully crowned and anointed king of Bohemia. However, this hope was not fulfilled, as subsequent events were to show.